SUMMARY

US-based accelerator Y Combinator has been shifting the headquarters of its India portfolio companies to the US

While the HQ flipping is done to cut down the time spent in paperwork and regulatory procedures, Indian investors are crying foul over this practice

Early-stage investors already present on the cap table of YC-selected startups face extra administrative and legal burden due to HQ shifting

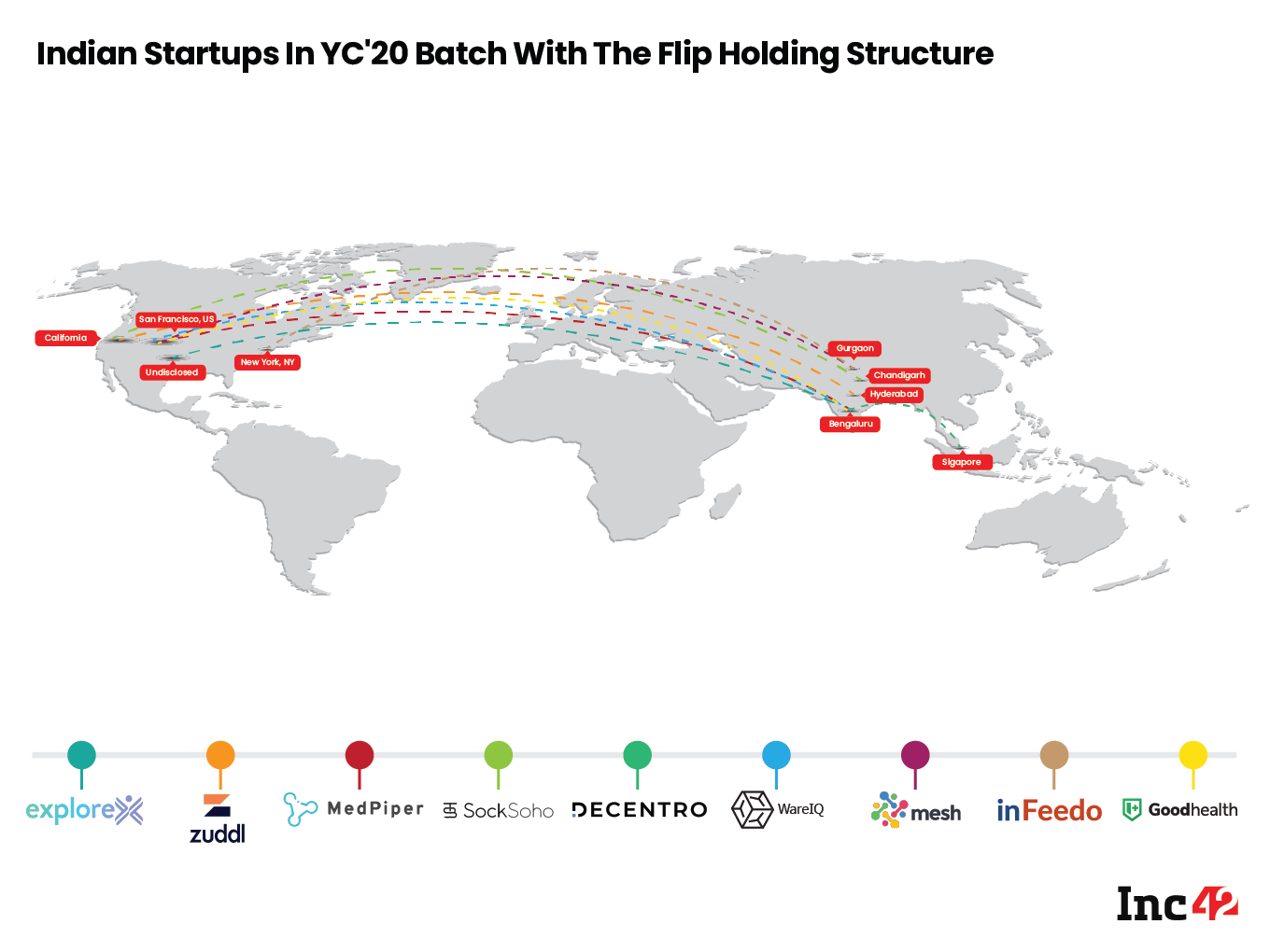

US-based startup accelerator Y Combinator’s (YC) decision to ‘flip’ Indian startups into American entities for the purpose of funding is facing backlash from early-stage investors and founders alike. Startups set up in India but selected for Y Combinator’s 2019 and 2020 batches are mandated to shift their headquarters to the US, which essentially ‘flips’ their India-registered entity into a wholly-owned subsidiary of a new US parent, Inc42 has learnt from founders and early-stage investors who have invested in YC-selected startups.

Several early-stage investors with whom Inc42 had spoken, raised concerns over the shifting of startup headquarters from India to the US, which would increase administrative and legal costs. This could have been avoided had Y Combinator directly invested in the Indian entities.

Sanjeev Bikhchandani, executive vice chairman of the digital behemoth Info Edge that owns Naukri, Jeevansaathi, Shiksha and 99acres (the holding company is currently listed on the New York Stock Exchange), said on Twitter that Y Combinator’s demand of flipping India-incorporated startups to the US is an “institutionalised transfer of wealth”. He also likened the flipping of headquarters to the exploitation of Indian intellectual property (IP), where YC gets to gain from the IPs developed by Indian founders.

“So you have a bunch of foreign investors who tell our best young startups that they will invest in their companies provided they shift their company domicile overseas. The reason being that they do not want to be subject to Indian laws, taxes and government rules except to the minimum extent required (because) they say they do not trust the Indian government and the legal system. So the ownership of the startup, the intellectual property (IP) and data all shift overseas. However, other operations continue as before; they build their products in India as before using Indian manpower; they sell to customers in India as before,” Bikhchandani told Inc42 in an emailed response.

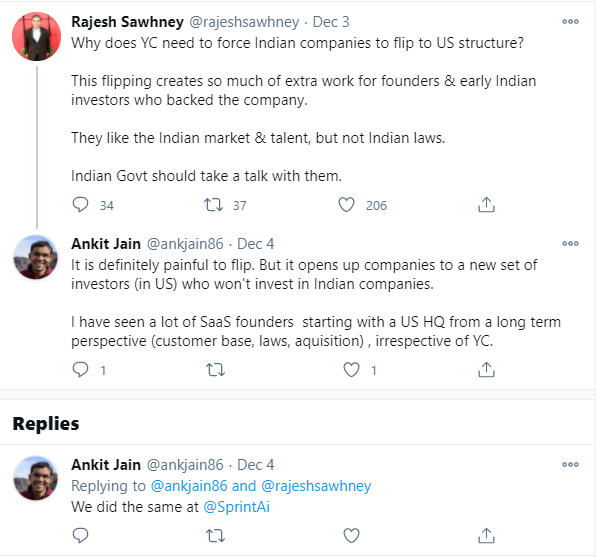

Bikhchandani’s backlash came after Rajesh Sawhney, the founder of GSF Accelerator, took to Twitter, saying that the flipping of headquarters “creates so much of extra work for founders and early Indian investors who backed the company (before it went to YC)”.

“They like the Indian market and talent, but not Indian laws… The Indian government should take the talk (have a conversation) with them,” Sawhney added in his Tweet.

While some of these concerns seem to paint a grim picture of an alleged brain drain of Indian entrepreneurs, the reality is that India’s incorporation and taxation laws have not been exactly friendly to startup investors and founders, especially to those in the early-stage ecosystem.

There are plenty of examples. When the coronavirus pandemic hit India in March this year, the “angel tax, which is levied on non-listed companies (such as startups), made a comeback, even after the Indian government had abolished the controversial tax on paper.

Besides, the ESOP tax, which puts the burden of double taxation on startup employees holding equity shares, was supposed to be abolished after Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman addressed the issue in this year’s Budget presentation. But the burden of double taxation continues to plague Indian startup founders and employees as only a few government-recognised startups can claim tax reliefs.

Although Indian taxation laws may seem unfavourable to investors and founders, many early-stage backers are far from happy about Y Combinator’s recent mandate to Indian founders on headquarters shifting. According to Kushal Bhagia, chief executive of early-stage fund Firstcheque.vc, early backers of those startups will face huge legal challenges when the companies in question get restructured.

So, what will be the most pressing issues?

The ‘Flip’ Process Explained

First of all, the Indian entity in question would have to be reclassified as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the foreign entity, and it would have significant administrative and legal implications for the existing investors or shareholders of that startup.

“After creating the US company, the founders and current investors (who have put their money into the Indian entity) would have to be ‘gifted’ some shares of this new U.S. entity for a nominal amount. Next, the US entity (of the startup) will have to open an Indian subsidiary that will carry out all essential operations like hiring employees or building products. Interestingly, the U.S. company will own the IP (intellectual property) and the brand, and will have a service agreement with the Indian subsidiary through which it will pay for the cost of operations with the money raised outside India,” explained Bhagia.

Another early-stage investor from a prominent venture capital fund told Inc42 how things panned out when his portfolio company was selected for Y Combinator’s backing. His lawyers suggested shutting down the Indian entity into which he held shares and shifting those to a new Indian entity. This had to be done to cut down on legal and regulatory costs arising for early investors as the existing Indian entity was already earning revenue from its operations, and had a predefined shareholding structure in place.

“Replicating the existing capitalisation table in the main parent company in the US after the flipping requires a lot of paperwork. At times, especially when the Indian entity already has some revenue operations in India, there are certain challenges if you suddenly classify it as a subsidiary,” adds the investor quoted above, asking not to be named.

According to Bhagia of Firstcheque.vc, the previous (Indian) company where Indian investors held shares will have to be shut down due to the flipping of headquarters from India to the US.

“All India-registered alternative investment funds (AIFs), which have invested in that startup, will have to apply to the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) for approval before they can invest even a token amount in the US company. And the whole thing will take months,” he added.

Bhagia, however, pointed out that many Indian founders choose to incorporate their companies in the US or Singapore due to several advantages, including the ease of fundraising from foreign investors and the ease of doing business with foreign clients.

“Companies selling (products and services) to enterprises abroad have an advantage if they are registered in the US as enterprise customers prefer working with U.S. firms,” he added.

The largest exit in India’s startup space – Flipkart’s $16 Bn acquisition by Walmart in 2018 – was routed via Singapore as Flipkart’s parent company which was registered in Robinson Road neighbourhood in that city-state.

Legal experts say that Indian tech startups are increasingly registering in the US, and other foreign countries as new founders get easy access to global funds in that way. If one is a founder with a long-term exit strategy, incorporating the company abroad is a default option.

Shantanu Surpure, a partner at California-based law firm Inventus Law, told Inc42 in the last decade alone, more than 100 technology startups and companies from India ‘chose’ to register in the US, Singapore and other foreign geographies. According to him, attracting funds from global investors is a big motivation for Indian tech companies incorporating abroad. Surpure is a corporate lawyer based in California who has more than two decades of experience in cross border deal-making focused on the US, UK and India geogrpahies.

“Even if you go way back to the early 2000s during the early software era in India, one of the biggest exits at that time was Genpact, which was a BPO company which was listed on NYSE in 2007 and that company was incorporated in Bermuda. India tech and software companies have been doing this global restructuring for a long time, especially in the last 15-20 years,” added Surpure.

Rahul Mathur, the founder of the insure-tech startup BimaPe, told Inc42 he had voluntarily registered his startup’s parent entity in Delaware, US, especially after his first round of fundraising was pledged by a foreign investor. It made things easier for him to allocate the funds into his startup. Before the external fundraising, Mathur had registered his startup in Mumbai, which is now a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Delaware entity.

“We do ‘transfer pricing’ for whatever payments we need to make (salaries, vendors’ payments and so on). We have an Indian lawyer for the Indian company and a foreign lawyer for the Delaware corporation. However, we expect the subsidiary firm in India to get an insurance brokerage licence in the future,” said Mathur.

Transfer pricing refers to the price (tax) that has to be paid when capital goods or services need to be transferred from one unit of an organisation to another unit located outside the geography of the parent company. These taxes have to be paid every time there is a movement of capital or payments have to be made to vendors outside the parent entity.

Some investors, however, point out that transfer pricing does not ensure that the IPs created by the Indian founders will be utilised in India technically.

“Whether you raise money in the US or Singapore, your employees (expenses) are going to be registered in India, which essentially means the Indian entity is going to be your offshore development company. It is almost as if your IP now belongs to a US company, and India just becomes an offshore development centre. But ideally, the Indian entity should be holding the IP, as well as the revenue, from product and service sales,” said the VC quoted earlier in the article.

However, Surpure of Inventus Law points out that in the eCommerce and consumer Internet space, there is very little room for creating unique IPs which are patentable.

“There are few IPs from India in the deep tech space which might be patentable. Otherwise, the IP is software code, trademarks and domain name. It is the business model which might be unique but not the IP per se. Perhaps some of the IP is assigned to the parent US company but essentially India does benefit economically because the employees and founders are largely in India and the money does come back into India,” adds Surpure.

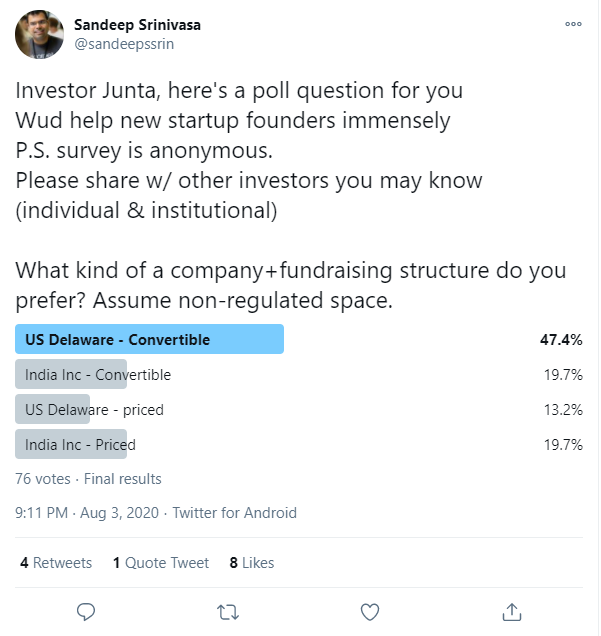

On Twitter, several founders and investors have also offered different perspectives as to why many of them choose to flip to foreign geographies in spite of early-stage investors crying foul over the practice.

But Bikhchandani of Info Edge did not agree. He told Inc42 flipping headquarters of an Indian startup to a foreign nation is the “act of externalising a company” where the startup has to transfer ownership of all its shares to an overseas firm that has only been set up to move shares around. If such flipping takes place on a massive scale, the country (India) might end up with a situation where the startups, the investors, the IP and the data are all domiciled overseas with little accountability to Indian regulators, he added.

“If 500 of our best startups have shifted overseas and 2% of those become as successful as Naukri and half of that (2%) become as successful as Infosys, we are talking about a future loss of more than INR 17 Lakh Cr in market cap at current prices. These companies will operate in India and access the market. However, they will not be Indian companies. A domicile shift and transfer of IP and data to an overseas company is a permanent loss. As a company grows, so does this loss. Remember that HCL and Infosys were startups in the early ’80s. Imagine what would have happened if they had flipped overseas when they were young. This is a matter of strategic significance for India,” says Bikhchandani.

Responding to Inc42’s queries, a spokesperson from Y Combinator said that besides the US, the accelerator also allows a startup to register its parent entity in Singapore, Cayman Islands and Canada, and this requirement is stated in the accelerator’s application materials and acceptance communications.

The accelerator also said that it chooses new jurisdictions (territories) for startups’ parent entities based on several factors. These may include investors’ requirements, analysis of tax consequences of investing in those jurisdictions, administrative considerations (for instance, whether electronic signatures are accepted in that jurisdiction or everything has to be ink-signed/notarised), similarity to the US model of corporate structuring (so that YC’s internal legal team can understand the documents and the structure) and the use of English language (so that YC’s representatives can read and understand the documents).

“We have invested directly in an Indian entity once, a company that was unable to create a non-India parent firm due to Indian restrictions on foreign ownership. It happened because of the industry it was in – that space is heavily regulated in India. A second direct investment in India for a company that was in a similar position was rescinded because the founders were able to figure out how to structure a US parent,” the spokesperson added.

Although many Indian investors are not comfortable with recreating their shareholding structure abroad whenever their portfolio startups flip, only a founder can make the ultimate decision to this effect. As pointed out earlier, that decision is made after carefully considering all prospects such as a favourable exit, easy access to capital and the ease of doing business.

Even though a ‘swadeshi’ movement to build in India is laudable, one has to keep in mind that billion-dollar and trillion-dollar companies are not made without significant global appeal. An Indian startup may have its roots in Koramangala or Gurugram, but it has to strive to serve customers globally to reach higher valuations and earn bigger revenues.

Note: The article has been updated with tweets, and perspective from the point of view of startups founders, and a comment from a legal expert has been added to explain why Indian startups incorporate abroad.

Correction Note:

December 8, 2020 | 16:00

A previous version of this article erroneously claimed startups were being forced to turn into wholly-owned subsidiaries of Y Combinator. This error has been rectified and the latest version of the article reflects these changes. We deeply regret the error.