India’s online grocery startups are battling to achieve the fastest delivery time. Who will come out on top?

Dear reader,

There’s every chance that you are now a customer of online grocery delivery — even if you weren’t 18 months ago. But the market has changed so much since last March that online grocery players have to look beyond availability of new products or discounts to gain market share. The competition has now boiled down to how quickly deliveries are made.

This week, the online grocery race turned into a sprint from a marathon, with startups looking to one-up each other by promising shorter delivery times.

It all started with Swiggy, which promised deliveries in 15-30 minutes through its InstaMart service. Days after Swiggy, Grofers said that it plans to launch 10-minute grocery deliveries in 10 cities. And then Dunzo followed it up by promising deliveries in 19 minutes in Bengaluru through its Xpress Mart dark store network.

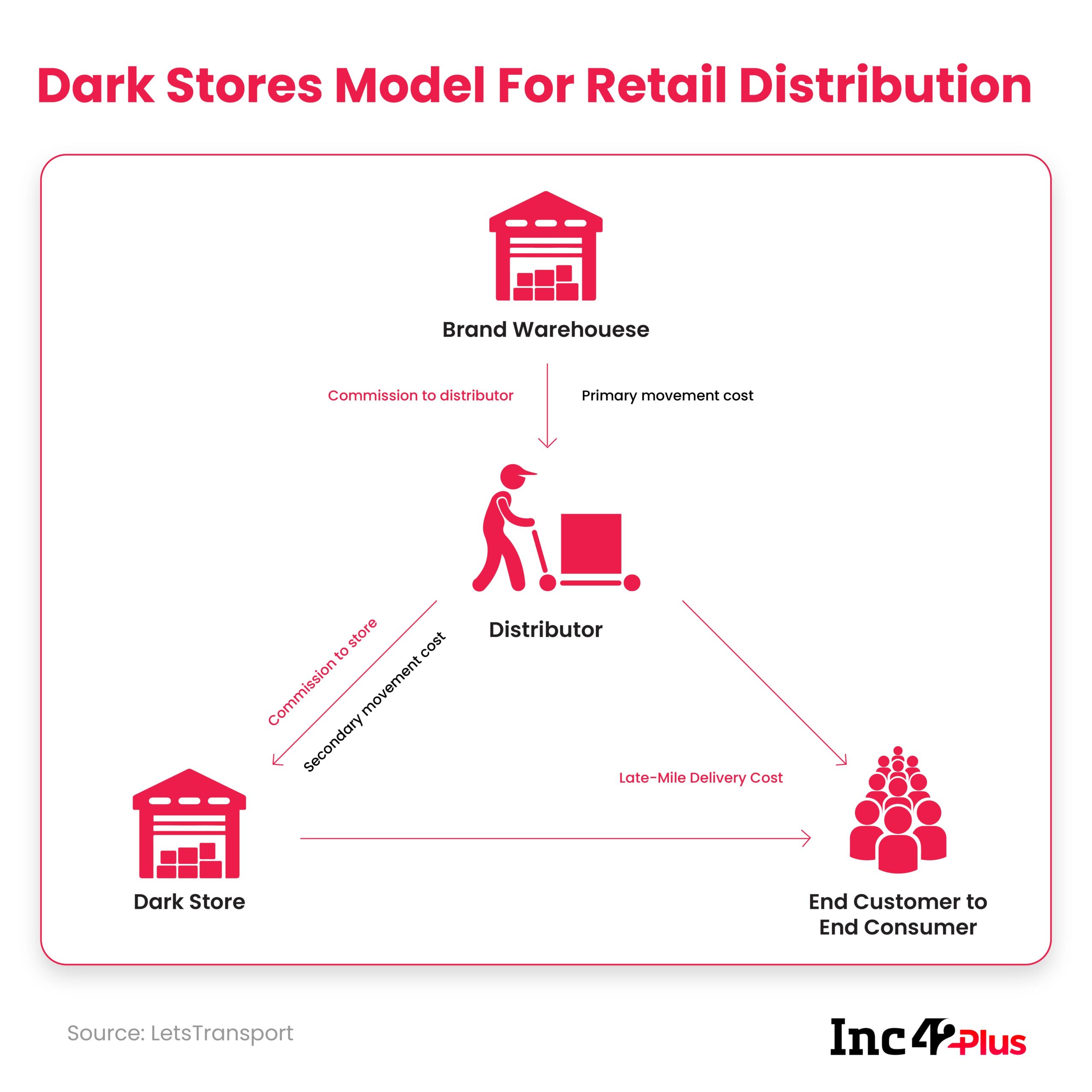

Built on the back of the dark store model, the rush for grocery and essential deliveries is just beginning. Simply speaking, a dark store is a small neighbourhood warehouse where consumers cannot enter directly and can only order online for a home delivery. Grofers said it would use dark stores in residential neighbourhoods to fulfil the 10-minute delivery promise.

Grofers’ announcement comes after Swiggy said it would expand Instamart hyperlocal grocery delivery to five more cities, claiming to fulfil deliveries within 15-30 minutes. Not far behind, BigBasket offers BB Express, which promises deliveries of essentials in 60 minutes.

Dunzo, which has expanded its Dunzo Daily for groceries and other household items to cover all of Bengaluru, was already one of the faster delivery services, given that its riders typically service a particular neighbourhood in a city. This has now been coupled with dark stores for even faster deliveries.

In a conversation with Inc42 in May this year, Dunzo cofounder and CEO Kabeer Biswas said the company plans to clock a $200 Mn GMV run-rate by the end of the current financial year (FY22). And one of the ways to achieve this was by owning the inventory. Dunzo has been bullish on the increased dependency of consumers on delivery apps due to the ongoing pandemic that has kept people inside homes for more than a year now.

Of course, it’s not just hyperlocal grocery delivery players that are racing to achieve the fastest delivery time. Since 2019, Amazon India has promised deliveries in two hours under Amazon Fresh, which it has expanded to more cities in 2021. Walmart-owned ecommerce giant Flipkart is also claiming a similar delivery time for groceries under its Flipkart Quick service, which it launched last year amid the lockdowns. Now both companies are heavily marketing the grocery delivery within their apps.

While in the years before the pandemic, setting up a dark store network involved plenty of overheads and high operational costs, the new normal that has set in since February 2020 has changed the perspective on these dark stores, because the need now is to meet consumer demand as soon as possible.

As per our past conversations with logistics and retail tech players, the cost of quick two-hour or four-hour delivery through dark stores comes at almost 40% higher cost than the traditional warehouse model in India. This makes dark stores difficult to scale for the price-sensitive Indian consumer and business, but the Covid-19 pandemic has created a positive momentum for hyperlocal delivery players serving the essentials segment.

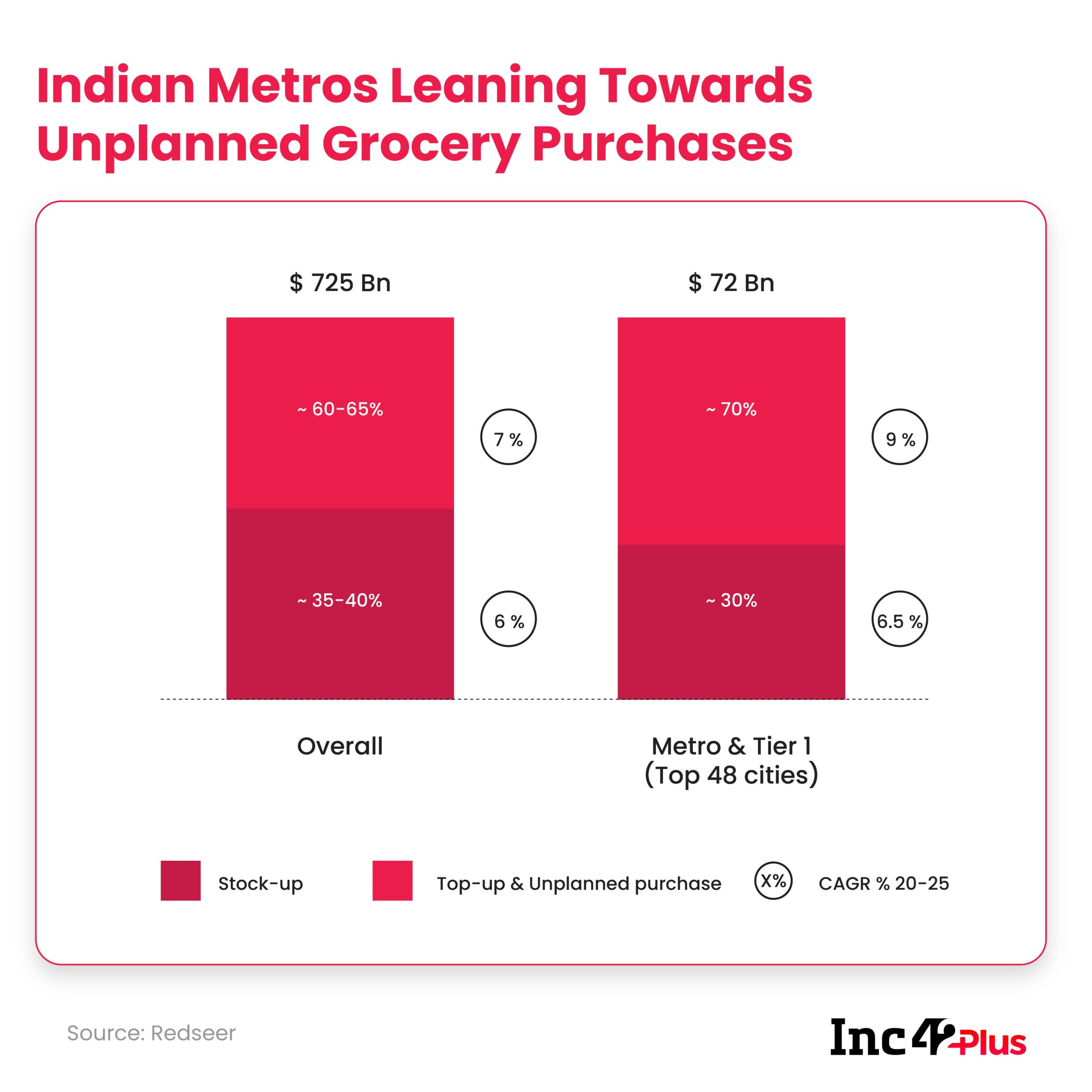

The changing attitudes of customers in metros and Tier 1 cities towards online grocery shopping is the primary motivation for the rapid deployment of dark stores by ecommerce players. These dark stores not only allow delivery companies to control the inventory, but also get deeper insights into what product categories or individual brands have the highest adoption. This in turn is helping many of them, including BigBasket, Flipkart, Amazon India and Grofers to expand their private label plays.

But there’s another question that comes up in the face of delivery platforms adopting dark stores. Will these stores end up replacing kirana shops and grocery stores that have been the backbone of the online grocery market so far?

Will Kiranas Be Sidelined In Dark Store Push?

The digital transformation wave in local retailers and kirana stores has spawned the category of ‘dukaan tech’, which could be left on the sidelines if indeed online grocery becomes a dark store-centric play.

Till last year, kiranas were seen as the enablers for grocery delivery and that’s the model that Grofers, Zomato, Dunzo, Swiggy and others adopted when adding grocery delivery services to their repertoire last year. In 2021, however, now that the market for online grocery delivery is more or less established given the transition to ecommerce, delivery startups are focussing more on unit economics and value-addition.

From a unit economics point of view, dark stores allow companies to manage their delivery operations through a hub and spoke model — with a large warehouse or the hub run in conjunction with smaller dark stores or the spokes. This means that distribution can be streamlined to a particular dark store that needs the supply.

Consequently, last-mile deliveries from dark stores can be made more efficient by stationing delivery riders at these dark stores rather than having them spread out over a neighbourhood, going from store to store.

As for value-addition, the quick delivery promise is the biggest advantage for consumers, but there will be questions on quality and availability of products. Delivery companies have to ensure that dark stores have the most commonly-ordered products and therefore may not be able to offer a wide variety of items. There are questions about the overheads for storing perishable goods at these dark stores as well, something which delivery companies don’t have to contend with right now, by leveraging existing kiranas and stores which already have these facilities.

Meanwhile, Zomato has completed its stake acquisition in Grofers after getting the approval from CCI. Overall, Zomato is shelling out $100 Mn for a 9.1% stake in Grofers India, as well as the acquisition of its B2B wholesale subsidiary Hands on Trades Private Limited (HOTPL), which will tie into Zomato’s Hyperpure B2B vertical as well as its plans to add grocery delivery to its platform.

Metros Gravitate Towards Quick Commerce

The move to dark stores and deliveries in 15 minutes also begs the question of whether there is a real need for such ultra-fast 10-minute deliveries. The typical use-case for instant delivery would be getting grocery or household items in a pinch, and according to Redseer, the Indian market is seeing more and more unplanned purchases for online grocery, particularly in the metros and Tier 1 cities.

Billed as “quick commerce”, the recent report says that convenience and fulfilment time are key criteria for mid-to high income households in metros, especially those in the 25-35 age bracket.

Perhaps this changing landscape is what has attracted Tata Group to hyperlocal delivery startup Dunzo, after the acquisition of BigBasket. While Tata Group is seeking majority control of Dunzo, according to reports, the Bengaluru-based startup’s founders are not keen on giving up full control. Dunzo is also said to be in talks with investors for an infusion of $100 Mn-$120 Mn, which would allow the startup to expand its dark stores model to other cities too.

The Pressure Of On-Time Delivery

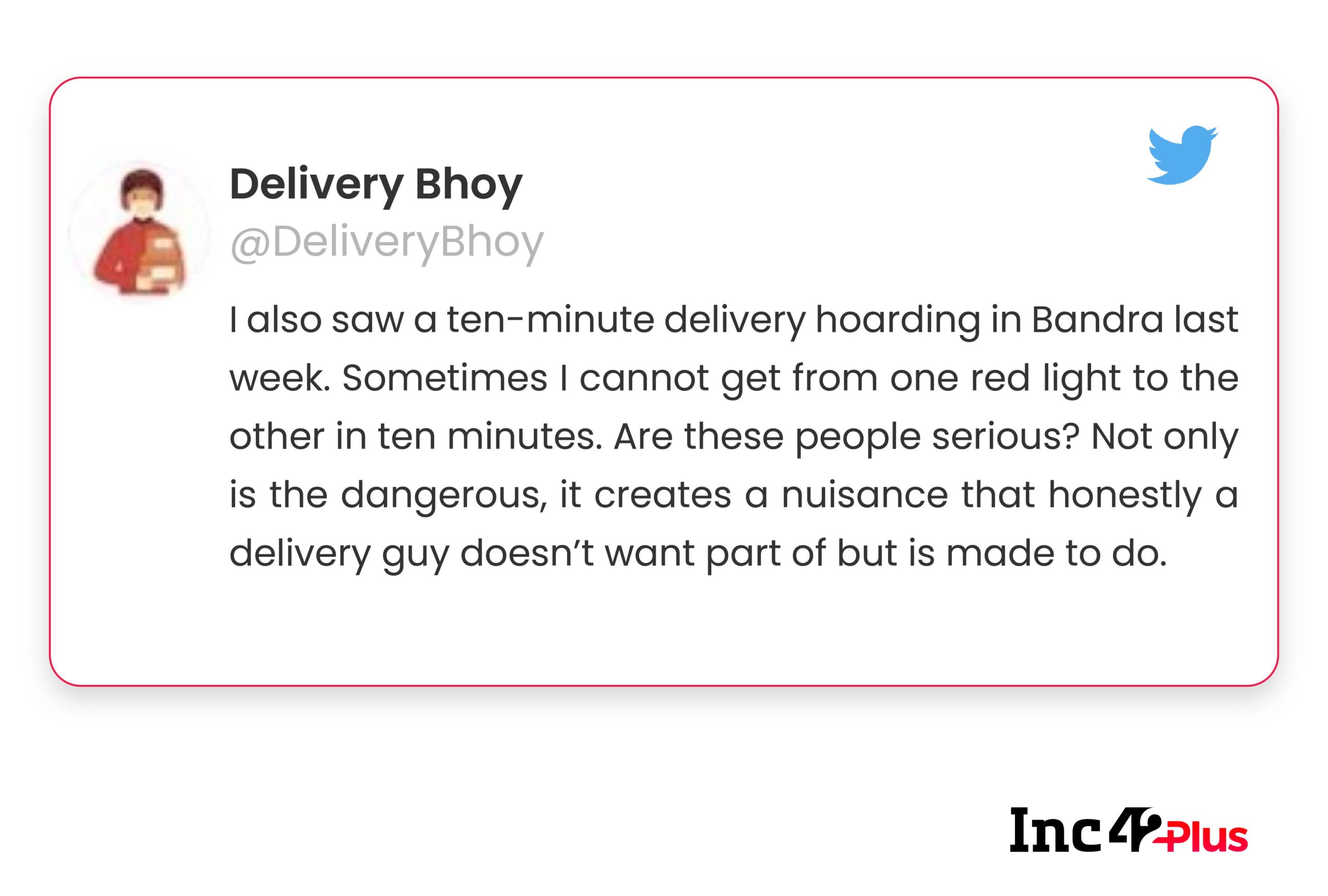

Dark stores will certainly allow delivery companies more flexibility, but in the race to achieve the lowest delivery time, delivery partners will also be under pressure to fulfill orders in the promised time. Social media is already rife with anonymous accounts whistle-blowing on some of the delivery-related policies by Swiggy and Zomato.

Major complaints include petrol prices, absence of pay when covering the first mile between home and restaurant, lack of clear incentives, arbitrary fee deductions, and limits on daily earnings. Besides this, the delivery partners have also complained about the fact that neither Zomato nor Swiggy provide them compensation for the free ‘advertising’ that they do with the uniforms and branding on the vehicles. The rush for quick deliveries will pile on the pressure on these riders.

Delivery riders could end up being penalised if they do not fulfil the orders within this short window. In its terms for delivery partners, Zomato explicitly states that the company shall not be held liable for any accidents or incidents involving the delivery partner in the course of delivering orders, and that the partner will indemnify or compensate Zomato for any losses “as a consequence of any complaint from any User and/or Restaurant Partner received by Zomato with respect to any error or deficiency in the Delivery Services.”

Similarly, Swiggy says it is not responsible for the services provided by its pick-up and delivery partners (PDPs) to its customers. “Upon acceptance of any Order or Task by the PDPs, the pickup and delivery services or Task completion services (as the case may be) undertaken by him/her, shall constitute a separate contract for services between Merchants/Buyers and PDPs.”

Companies are washing their hands off the responsibility towards delivery partners, despite promising delivery times that may not be possible to fulfil in most major metros. Given that cities like Bengaluru, Mumbai and Delhi are renowned for their traffic jams, will grocery delivery partners end up as disenfranchised as their food delivery counterparts?

Till next week’s delivery,

Nikhil Subramaniam

Featured image and graphics: Ajay Singh

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/featured.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/academy.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/reports.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/perks5.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/perks6.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/perks4.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/perks3.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/perks2.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/perks1.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/twitter5.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/twitter4.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/twitter3.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/twitter2.png)

![[The Outline By Inc42 Plus] Digital Grocers & Their Need For Speed-Inc42 Media](https://asset.inc42.com/2023/09/twitter1.png)

Ad-lite browsing experience

Ad-lite browsing experience