With so much focus on technology in the classroom, schools are under pressure to invest more in gadgetry

While teaching is turning to digital tools, students are still tested through analogue exams and standardised grading

Does an increased focus on tech and digital learning necessarily equal improved learning outcomes?

India's Edtech Moment

Technology is upending the traditional ways of teaching and learning. What does the future of education hold?

[This is a free preview article of our 6-part ‘India’s Edtech Moment’ Playbook, as part of Inc42+ (our membership programme). In this playbook, we are diving into the world of edtech, which is transforming India’s education system and catapulting it into the 21st century. Click here to read the complete ‘India’s Edtech Moment’ Playbook.]

“I am forty and employed in a job which does not have much growth potential. I want my kid to ace the competitive exams. Make him a rocket scientist or a doctor or anything which will give him immunity to automation in 10-15 years.”

Beas Dev Ralhan is used to hearing parents parrot this line. Ralhan, cofounder and CEO of Next Education, has heard parents’ worries and laments about their kids’ futures on a near-daily basis for years. As the once distant threat of automation becomes a clear and present danger, perhaps jobs for rocket scientists and doctors are at least somewhat resistant to being taken over by robots — the keyword being somewhat.

For Ralhan and other educators like him, the frantic parents are a sign of the fight to stay relevant in the 21st-century job market. Technology is seen as the saviour, but how much of it is actually useful in the Indian context?

The task of predicting the future is herculean for educators as each year a new set of parents has different expectations and demands. It also doesn’t help that exposure to newer methods of teaching and learning outcome measurement has forced parents to look for schools and tutoring that emphasise technology. While some parents demand that private schools let students explore their interests instead of simply focussing on rote-learning, others are urging schools to just focus on the most basic outcome — test results.

Ralhan, whose company Next Education is a K-12 edtech solutions provider, said this makes the business of primary school education a tough nut to crack.

Businesses are run on hard numbers and the assumption of rational customers, while the initial years of schooling are anything but that. Caught between parents’ expectations, standardised tests, an uncertain future of jobs and a reluctance to change a 100-year-old approach to pedagogy, the future of classrooms in India’s top private schools is as confused as some of the kids sitting in them.

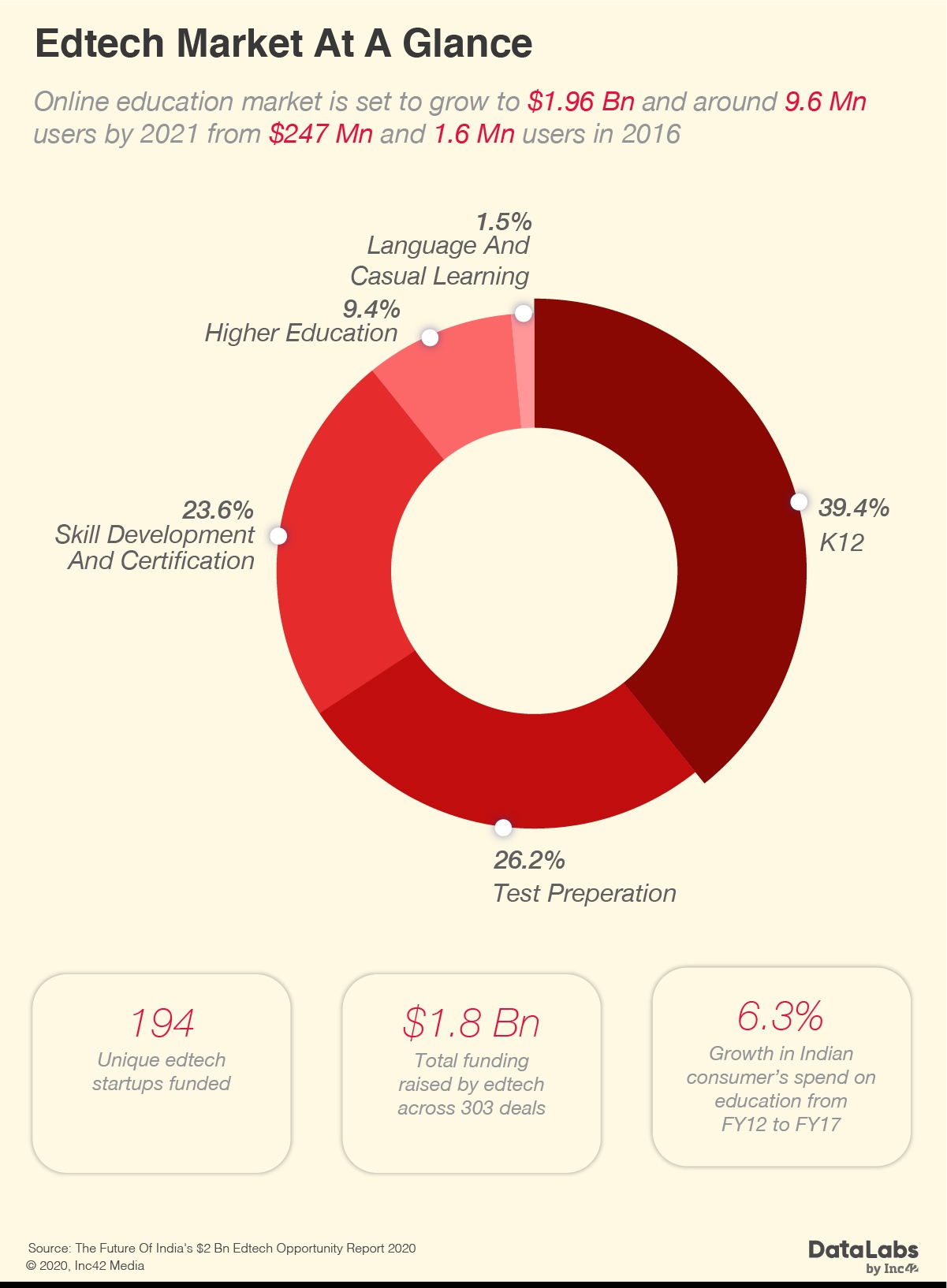

Depending on who you ask, the vision for the future of education varies wildly. Tech companies betting big on what will be a $100 Bn opportunity (in India alone) this year, are perhaps the most vocal of the lot. The fact is that India has the largest number of schools and school-going kids and no clear idea of how to match international standards of mathematical ability, scientific reasoning, comprehension and language skills.

All this makes India a prime breeding grounds for techies and marketers with very little skin in the game to sell their version of the future of the classroom.

From hardware makers with interactive whiteboards at ten-times the cost of a humble blackboard (RIP) to pushy purveyors of tablets crammed with video content (looking at you BYJU’s) and savvy marketers waxing about the latest outcome-oriented solutions with AI and machine learning algorithms, edtech startups come in all shapes, sizes and models today.

Edtech startups promise free and open access to knowledge, transparency and constant feedback, gamification and outcomes. They claim everything short of downloading the lessons into a child’s brain — many claim palliative qualities that are simply vaporware. So how are parents and teachers supposed to find common ground in this?

Is there a place for real learning in the edtech startup’s vision of gadgetry-driven consumption, video watching and interactive games? Does it actually deliver better results among students than good ol’ cramming? And at what cost?

The Old King Is Dead; Long Live The King

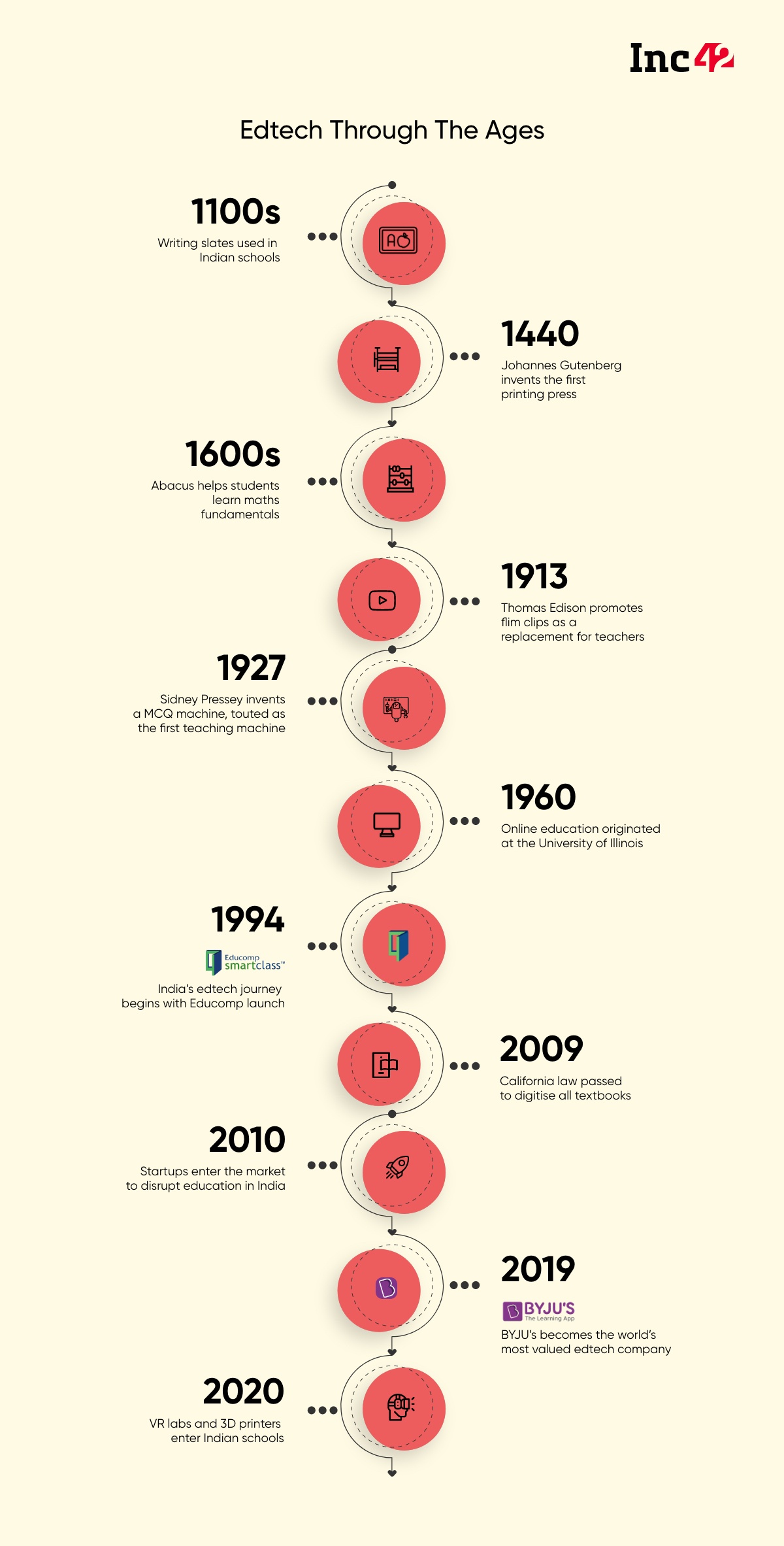

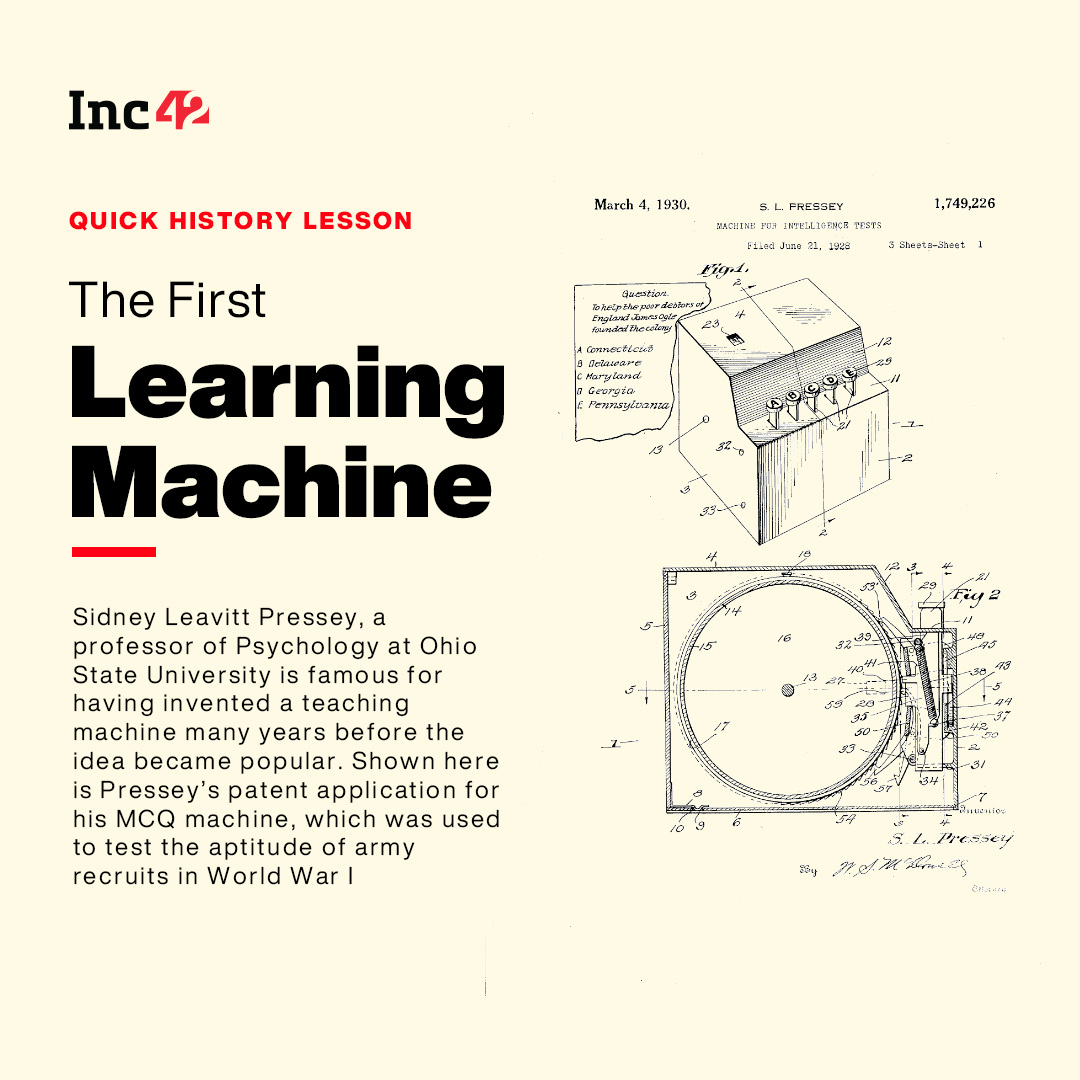

The problem with the edtech vision for the future of education is that it borders on a retelling of its past. Flipping through pages of history, these so-called educational breakthroughs and ideas being peddled today are not new.

Consider this: Thomas Edison predicted in 1913 that “books will soon be obsolete in schools”.

Edison’s reputation as a businessman far outshine his prowess as an inventor, so it might have made business sense to the entrepreneurs of the time but unfortunately, this vision did not come true for the next few decades. Edison, incidentally, had invested in motion picture technology at the time, which was the precursor to video and then digital media. So in a way, the BYJU’s model was first floated over 100 years ago.

The last hundred years of pedagogy’s rich history is littered with such claims of tech breakthroughs and visions — slide projectors were all the rage in the 1950s, online education took root at the University of Illinois in 1960 (though the internet was still nine years away), and by the 1980s, most university libraries were digitised. In 1994, the first online high school Compu High was founded. But the revolution is far from apparent.

Educational films were going to change everything. Teaching machines were going to change everything. The internet was going to change everything. The refrains of today’s edtech platforms sound borderline amnesiac if taken in this historical context.

But this has not deterred the other two big stakeholders of this industry — educators and parents — from trying to integrate tech into the classroom.

“Things have changed but not by much. Tech is available for everyone and it is easy to build smart classrooms but the minute these panels or projectors are switched on kids take it as TV show,” said Vijaya Lakshmi, a teacher with 30 years of experience in Delhi’s private schools.

Picture the vision of the future painted by today’s edtech companies — kindergarteners are putting on virtual reality headsets and using augmented reality to learn the alphabet and numbers. Homework consists of watching a few videos as a camera tracks your eyes for engagement and distraction. Textbooks are relics of the past, unknown to most young learners as everything is digital — including notebooks. Real labs are replaced by AR-powered virtual labs where students can mix chemicals or see the human anatomy in breath-taking 3D detail. And yes, some schools have even replaced the morning roll call with facial recognition to mark attendance.

When broken down in this manner, the classroom of the future seems more dystopian than utopic.

And many wonder whether any of this technology is actually doing any good. Nevertheless, those who run schools have the unenviable job of trying to please parents who seemed to have bought into the edtech pitch gleefully. Despite the different opinions on technology in the classroom among parents, many schools seem to think introducing technology will automatically future-proof them. It also does not help that a big onus of the child’s performance is on schools, so the pressure from parents who want technology wins the day.

But as educators we spoke to told us — good results are more a function of the quality of education, not the amount of investment that’s gone into the infrastructure nor the technology that delivers the lesson. So schools are facing a larger question of how to blend technology into the classroom experience in a meaningful manner.

“In the future, a platform that provides content, or does a modicum of personalisation will not be enough. A deep understanding of how best to teach and innovation in the way one learns will lead to better learning outcomes of the future, as tech and connectivity are becoming cheaper,” said Manan Khurma, CEO and founder, CueMath, which works with school students on mathematics training online as well as through in-person coaching.

So what is stopping schools from giving up the forced implementation of tech in many cases and adhering to the best version of school education? Two words.

Parental Pressure

In India, educators and operators of elite schools (typically the ones with the money and the will to adopt newer methods) are caught between two sets of parents. While the first comment is typical of parents that want schools to buckle down on their kids early on so that they can get “good jobs”, there is a second set of expectations from parents that want education to focus on more than just curriculum — they want holistic learning and development. Other parents look at schools for foreign colleges and get a more “rounded education”.

“Schools today will have to decide which category of parents they are catering to,” Ralhan of Next Education said.

There’s a well-established hierarchy of public schools, grammar schools and private schools in other countries, Ralhan pointed out. “In the UK, all the middle-class kids go to public schools. Out of those, the brilliant ones go to grammar schools which are almost as good as private schools and the rich kids all go to private schools.”

Despite this, 70% of the jobs which pay more than $100K per year go to people who have studied in private schools, he added.

This means that India’s elite schools, most of which focus on homogenising the standards and quality of education across a large spread of the population, will soon have to create specialised facilities depending on what the parents want. Problem is parents themselves are uncertain about what sort of skills their kids will require 10 to 15 years from now.

Past Continuous, Future Tense

“If you see the number of Indian schools which are truly embracing technology, the number would be around just 2000 schools across the country. 3000, if we are being generous,” Amol Arora, the managing director of Shemford and Shemrock group of schools told Inc42.

That’s the tiniest of fractions from the 1.5 Mn schools in India currently. So when one talks about technology in primary education, one is barely scratching the surface.

That technocentric future is still a few years off if not a whole decade away, Arora indicated. Edtech, of course, is not immune to the same challenges that other tech-centric sectors and models face. That of shrinking digitisation as they attempt to widen the base. And with edtech the situation is worse off in Tier 4/5 cities and semi-urban areas as school infrastructure is largely crumbling there.

As Pranjal Kumar, CFO and head of education fund at Bertelsmann, told us, “In our view, the failure rate for edtech startups is comparable with any other sector. Given that education is a high-involvement category and a career-affecting service, tech adoption is usually lower compared to other services and products. Hence, edtech startups can take more time to scale up than in some of the other categories.”

In the urban context, the inability to participate in outcome measurement — board certificate exams — is a big impediment for edtech penetration. While primary education is definitely better-off with the use of interactive lessons and personalised learning tools, the outcomes are shoe-horned into standardised tests across most systems of schooling.

According to BYJU’s COO Mrinal Mohit 2020 will be the year when learning goes ‘phygital’, which is just another way of saying, there will be more tech in classrooms. “Seamless offline-online integration will add a whole new dimension to digital learning and key to delivering impactful learning programmes. The environment will be conducive to a homogenous format of learning, which will translate into learners learning while they are doing,” he told us in an earlier interaction.

Edtech Can’t Get Rid Of Exams

In fact, all the schools and teachers that Inc42 spoke to said that very little had changed in terms of board exams being the focal point for parents and competitive entrance exams being the next step in the journey for a student after school. It’s the kind of sad ground reality that technology cannot change, no matter how engaging the content or how cleverly it’s packaged.

As Lakshmi told us, CBSE now emphasises on experiential learning but it is mostly ineffective as the question papers have not changed much in the past two decades.

Tech is also unable to step into the develop the interpersonal skills that a classroom builds in a student. It’s impossible for technology to imitate the friendships that blossom in school or to evoke the same admiration that a curious ward has for their teacher. These are the very real benefits of a school education, which are rarely spoken of, but which are perhaps the most important from the point of view of psychosocial development of a young mind.

This separation of holistic education from a useful one leaves it up to the parents to make the tough choice — the cold, hard approach with a focus on grades OR a flexible and open approach with a mix of digital curriculum, AR/VR lessons, interpersonal skill development and holistic learning. And sadly, the choice has nothing to do with the child’s interests but more to do with their parents’ social status.

Sabarinath Nair, founder of Skillveri, an edtech startup that uses augmented reality and virtual reality for skilling, told Inc42, “These technologies have to be seen as a means to an end, instead of an end in itself. A framework is to be used to decide if a particular content or concept will be better delivered through AR/VR, instead of mindlessly applying the technology for everything.”

The Edtech Class Divide

In India, where middle-class incomes are shrinking and quality employment is harder to find, the only hope for parents is that their kids jump to a higher social rung through a solid foundation in education. Considering that education has long-term effects which run from one generation to the next, Indian schools say that this change in business models from old-school learning to tech-driven lessons will definitely lead to deeper social polarisation and at a much younger age.

A 2008 report on the rise of private schooling had noted that “one important consideration in choosing a school is to form associations and networks that can help later in life” while describing what prompts students in US campuses to join fraternities and sororities.”

The report, which was written by Sonalde Desai, Amaresh Dubey, Reeve Vanneman and Rukmini Banerji, and reviewed by Nobel laureate Abhijit Bannerjee and edited by former Niti Aayog vice-chairman Arvind Panagariya, added:

“What the children or their parents will be paying for is partly the quality of education, but more importantly for the quality of associates the students are likely to find in this (private) school.”

If one was to put it more bluntly, it’s not what you know but who you know. Just try explaining that to a ten-year-old.

In fact, this somewhat thoughtless chasing of status markers has pushed schools to invest mindlessly in interactivity and technology, without a thought being paid to whether it’s actually having an impact. And schools are businesses too, that would definitely want to invest to earn bigger returns in the form of higher fees that such parents are more often than not willing to pay.

The move towards such a class division has already started, and while it would be imprudent to blame it on the reliance of tech, one cannot deny that technology is a big part of the sales pitch. The last decade has seen the rise of ‘International Schools’ in India, which routinely charge anywhere between INR 2 Lakh and INR 7 Lakh in tuition fees annually as compared to top-end public schools which generally charge half that, and public schools, which charge a fraction of that princely sum. With about 700 international schools, India has now outstripped China in terms of numbers of these premium institutions.

Big tech loves to yell disruption. In many ways, technology in education has democratised content and accessibility, but in other ways, it’s put children through a confusing maze as they try to understand what learning really is. Is it just watching a video, or is it about human interactions and teachable moments that one goes through in the classroom?

With inputs from Nikhil Subramaniam

Ad-lite browsing experience

Ad-lite browsing experience