"To become a $100 billion company, Flipkart needed a new vision, a new path."

Inc42 Daily Brief

Stay Ahead With Daily News & Analysis on India’s Tech & Startup Economy

The following piece is an adapted excerpt from Big Billion Startup – The Untold Flipkart Story by Mihir Dalal. Besides going deep into the background of how India’s largest ecommerce startup was made, the book also tells the story of how Flipkart founders — Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal — turned a small online retail website into a multibillion-dollar company.

By the mid-2000s, Amazon, the American online retailer, had emerged from the gloom of the dotcom bust, which had claimed hundreds of e-commerce and internet companies. But Amazon’s reputation – and stock price – were severely dented. It was seen as a mediocre technology firm.

In August 2004, the young search engine Google listed its shares, fetching a valuation that was far higher than that of Amazon. EBay, an online marketplace and auctions site and Amazon’s rival, earned higher profits and was considered a better-run company.

This may not have bothered Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos, who was known to be obsessed with keeping Amazon’s customers happy rather than worry about rivals or stock-market valuations. But there was one other goal that kept him occupied – he wanted to transform Amazon, a hawker of books, toys and electronics, into an all-purpose technology company.

As part of Bezos’ efforts to prove that Amazon was a ‘technology company, not a retailer’, the company opened its offices in the southern city of Bangalore. Its aim was to create exciting new technology products.

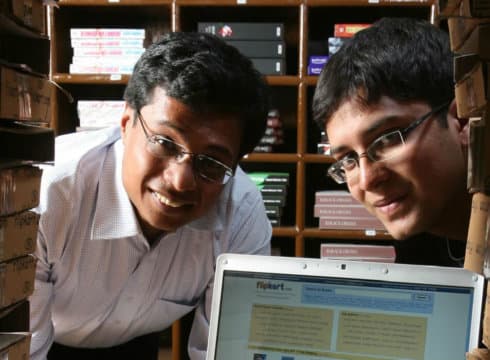

Among the engineers Amazon India hired in its early years were two graduates of Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi: Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal. In 2007, the Bansals quit their jobs at Amazon to launch an Amazon-like online retailer of their own. They pooled in Rs 400,000 of their savings to get Flipkart off the ground.

Their founding idea was simple: two Indian engineers could build a world-class internet firm of their own in India. As surprising as it may sound now, this was a contrarian view – in that period, internet entrepreneurship was considered a feeble initiative, doomed to fail. Many venture capital firms in India, despite being in the business of funding startups, didn’t believe in the possibility of large indigenous internet firms.

Seven years after starting out, the Bansals had definitively proved their doubters wrong. Flipkart had grown at an astonishing pace, becoming India’s largest e-commerce firm and its most outstanding internet startup. In July 2014, the company raised as much as $1 billion from Tiger Global, Naspers and other funds. When Sachin Bansal spoke after the fund raise, it was clear that he believed he was a man of destiny. ‘This is a big milestone not just for Flipkart, but for internet firms in India in general. We believe India can produce a $100 billion company [in sales] in the next five years, and we want to be that. Whether it takes five or ten years, we are here for the longer term.’

But there was one obstacle in Sachin’s path: Kalyan Krishnamurthy. Kalyan was a representative of Tiger Global, Flipkart’s largest investor, who had been sent on assignment as interim CFO to help turn around the company in early 2013. Flipkart had stumbled in the second half of 2012, as its sales growth slowed sharply and customer service suffered. Kalyan delivered what was asked of him: within six months of his joining, Flipkart’s business was thriving again. Though he had only joined as CFO, Kalyan had rapidly taken charge of a large part of the company. Apart from the finance department, he had been running Flipkart’s sales function, too, along with Binny Bansal. In the process, Kalyan and Binny had empowered the sales team and made it the preponderant function of the company. Kalyan, especially, had made it clear that the objective of the technology team was to support the sales and finance functions.

Sachin had watched Kalyan’s growing stature at Flipkart with increasing alarm. Their relationship wasn’t great. Kalyan clearly was a straight-up dhanda guy. He had little time for technological tinkering that didn’t provide a direct, immediate boost to sales. He thought of Flipkart as a retail business whose sole purpose was to grow its sales as fast as it could, through the most economic means, and thereby increase its valuation. Sachin, on the other hand, thought of himself as a technologist and inventor, and of Flipkart as a company that was using the power of software to offer a high-quality commerce service.

Their personalities, too, were mismatched. Kalyan sometimes travelled with Sachin for meetings with investors, recounting later to his friends that these were awkward trips, filled with long silences and conversations that ended as abruptly as they would begin. Kalyan was an extroverted leader who liked shooting the breeze with his trusted colleagues; Sachin was an inward-looking engineer, inherently awkward around people, whom he found less interesting than his video games.

Now after the $1 billion fund raise in 2014, his confidence soaring, Sachin set out to reinvent Flipkart.

In August 2014, Sachin called a small group of colleagues to his house in Koramangala. The agenda was to discuss what Flipkart needed to do so it could become a $100 billion company. He called the mission Flipkart 3.0. Sachin and Binny had led the company’s first phase, from its birth until the end of 2012. The second phase, dominated by Binny and Kalyan, had lasted eighteen months. It had been a great spell, one that had made the company into an efficient machine. But its time was up, Sachin believed. He also complained that this phase had introduced structural weaknesses that had to be undone. Flipkart had moved away from its technology mission. To become a $100 billion company, Flipkart needed a new vision, a new path. Now, he told his colleagues, the time had come for the company to undergo its biggest-ever transformation.

In a sense, history was repeating itself. Sachin’s initiation to the internet business had been with Amazon India, set up as part of Jeff Bezos’ efforts to prove that Amazon was a ‘technology company, not a retailer’. Nearly a decade later, Sachin was pursuing the same mission at Flipkart.

As conspicuous as those present at the Flipkart 3.0 meetings was the absentee: Kalyan Krishnamurthy, the man who was running much of the company – but this would have to change. In his mind, Sachin was clear about who would or wouldn’t have a place at Flipkart 3.0. It was clear to Kalyan, too.

ETERNAL STARTUP PROBLEM

Was Flipkart a technology firm? Was it a retailer? This battle over Flipkart’s identity – and the attendant personal conflicts – would eventually shape the company’s destiny.

But Flipkart is hardly the only internet firm to have asked this question of itself. As we’ve seen, Amazon struggled with the same question, though eventually, after the success of Amazon Web Services (AWS), the company was able to prove that it was indeed the most elite of technology companies rather than simply a retailing firm.

Still, this debate persists. For instance, is WeWork, the office-sharing startup, a technology platform? Or is it a real-estate firm? What about Oyo? Similar questions could be asked of Ola, Swiggy, Zomato and scores of other successful internet startups.

Going by Flipkart’s example, it would seem that an internet firm can be one or the other, but to try and swap one’s identity at will is a dangerous enterprise.

Mihir Dalal is an editor with Mint, from where he has covered Flipkart and other internet businesses for more than five years. He was born and brought up in Bombay and currently lives in Bangalore, where he has spent most of his professional life. Big Billion Startup – The Untold Flipkart Story is his first book and was published by Pan Macmillan India on October 6.

{{#name}}{{name}}{{/name}}{{^name}}-{{/name}}

{{#description}}{{description}}...{{/description}}{{^description}}-{{/description}}

Note: We at Inc42 take our ethics very seriously. More information about it can be found here.