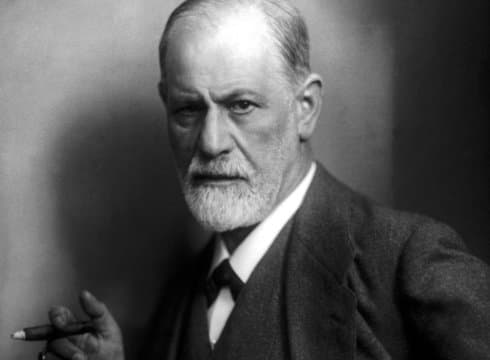

Sigmund Freud Pioneered Psychoanalysis, Believing In The Power Of The Unconscious Mind

Inc42 Daily Brief

Stay Ahead With Daily News & Analysis on India’s Tech & Startup Economy

He smoked cocaine, could speak seven languages – and as a boy, wanted to marry his mother. Sigmund Freud – both genius and quack – pioneered psychoanalysis, believing in the power of the unconscious mind.

While many of his theories have been put into question over the years – Freud’s advice on how we can improve our lives through changed thinking brings a fresh perspective to combat today’s battle with negativity, depression, and lack of meaning.

“Most people do not really want freedom, because freedom involves responsibility, and most people are frightened of responsibility.”

Freud’s words were perhaps never more accurate than today. Millions are playing the blame game, unwilling to take responsibility for themselves. But, as Freud accurately pointed out – once we do, we will feel incredible strength and freedom because we’ll become the master of our own fate. High self-esteem, confidence and a deep belief that we’re headed in the right direction all stem from our ability to grab the reigns. Wake up tomorrow knowing that taking responsibility will equal empowerment.

“Being entirely honest with oneself is a good exercise.”

Freud wanted all of his patients to be honest – about their past, their feelings, and their beliefs (no matter how painful). He reasoned that all of us are better at deceiving ourselves than we are of others (and as such, we are our own worst enemy). That self-deception can and does hold us back. We tell ourselves outright lies to avoid what we believe will be humiliation or disappointment. A key message for today from the mind of Sigmund Freud is that yes, you are good enough.

“Neurotics complain of their illness, but they make the most of it, and when it comes to talking it away from them they will defend it like a lioness her young.”

Freud believed that many people prefer to be miserable because negativity is the only thing they know. Today, science confirms that what we put into our mind is what will be reflected outwardly. Constantly putting ourselves down, watching violence or being in toxic relationships can transform us into an endless state of negativity. The unconscious mind, fed a regular diet of “wrong” thoughts will program accordingly. Freud believed that the unconscious is also able to hide repressed feelings and in so doing, can cause erratic and destructive behaviour, ending only once the buried feelings and thoughts are released. Let’s not forget to feed our unconscious mind with the right messages of self-love, adventure, learning and openness, to build our lives and careers.

Sigmund Freud was recognised as gifted from an early age. He was a top student. But Freud, who became the most famous psychologist in the world specialising in neurotic behavior – was himself neurotic as a boy – wanting to marry his own mother.

Freud looked upon his father as a competitor – someone who was in the way of winning his mother’s love and affection.

This early experience would later become part of Freud’s now famous theories – one of which he called “the psychic apparatus” in which mind functions are constantly at odds with each other, creating inner conflict. Our desire for love, happiness and a good life can often be short-circuited by self-destructive tendencies of self-doubt, aggression and violence.

Fortunately, for most of us who are mentally stable, Freud said that our life instinct (termed “eros”) is much more powerful than our destructive side (otherwise we would be on a fast track to death).

In the early 1900s, Freud created a “topographical model” of the brain in which he said the unconscious mind was much larger and more powerful than the conscious. In fact, so much so, that it is the unconscious mind running our lives, not the other way around.

(Freud used the terms “subconscious” and “unconscious” interchangeably because he believed people would be confused by the difference. The “subconscious” is easily accessible to us in the form of recent or strong memories. The “unconscious,” however, has data that is not easily accessible. It includes distant memories of childhood that ultimately shape our behaviour through life, as well as programming that allows us to do things without thinking about them).

Freud believed digging beneath the surface and letting out ideas, thoughts and memories – previously hidden in the unconscious – can help people cope and grow.

To explore the hidden mind, Freud developed the therapy that is still used today (in various forms including hypnosis) called “psychoanalysis” in which a patient is told to relax and talk about their dreams and childhood memories.

This type of therapy can go on for years.

But even without psychoanalysis, our unconscious thoughts can sometimes slip out (often embarrassingly) by something we say – revealing our true beliefs (now known as a “Freudian slip”).

Sigmund Freud did not create psychoanalysis but he did develop it.

The idea of having a patient talk to a doctor about their inner most feelings began with other, more experienced doctors, one of whom was a colleague and mentor of Freud’s named Josef Breuer. Breuer had a patient named Bertha Pappenheim (pictured here) suffering from hysteria with many unexplained physical symptoms such as paralysis and blurred vision.

But when Bertha talked to her doctor about some disturbing early life experiences (such as a dog drinking water from her glass, and caring for her sick father), her physical symptoms disappeared. It was upon learning of this that Freud went further than Breuer to study and develop this form of therapy.

While Freud was brilliant in the field of psychology, he was a fool when it came to his own physical health. It is said that he smoked as many as 30 cigars a day, claiming that smoking was “one of the greatest and cheapest enjoyments in life” and that he felt sorry for anyone who did not smoke. He ignored health warnings from colleagues.

Freud didn’t stop with cigars. He was also an avid user of cocaine for a period of two years, calling it a “magical substance” that helped him focus. He had hoped to market cocaine to the masses as an effective anesthetic drug to relieve pain (and become rich in the process).

But when the terrible addictive qualities of cocaine became apparent to Freud (who had also given it to his wife), he stopped using and promoting it.

While some of Freud’s theories are used today – others are generally regarded as nonsense or outdated. His belief, for example, that women envy the male sex organ – or that men are jealous of a woman’s ability to give life – are viewed as prejudicial thinking on the part of Freud and not anything scientific.

Today’s medical experts also look back on Freud’s research as flawed since many of his theories were never tested on a large number of people. In fact, much of his work was based on observing himself.

Freud had a cigar in his mouth on an almost 24/7 basis. Even after being diagnosed with cancer, he continued to smoke. He would later say it was one of the few joys of his life.

As a young man, Freud wanted to be a scientist but couldn’t figure out how to make any money at it. He chose to be a doctor, starting out with surgery, then psychology, launching a private practice specialising in “nervous disorders.”

But Freud was lonely, spending his nights reading the classics, including Shakespeare.

His loneliness would come to an end when, at age 30, he married 26 year old Martha Bernays. They would have six children and at first, during their engagement, the two were passionately in love. But Freud said the passion quickly disappeared almost the second the marriage began, overtaken by “practicality.”

Despite that, the marriage would endure for 53 years until Freud’s death.

Martha said of their marriage: “There was not a single angry word between us.” (There were rumors that Martha’s sister, who lived with Martha and Freud for a period, had grown close to Freud and had an affair with him. But historians have never been able to confirm this).

Martha lived a long life, dying at age 90 in 1951 (12 years after Freud).

Freud’s wife Martha smoked cocaine with him. (He told her it would add color to her cheeks).

Martha came from a respected, orthodox Jewish family and was expected to marry an established, wealthy man – not the penniless unemployed Freud. As a result, the two had kept their engagement secret. It was a passionate engagement with hundreds of love letters between the two. Later in their marriage, Martha (who was religious while Freud was not) would refer to Freud’s theories as “pornographic.”

In the mid-1930s, the rise of Hitler forced many Jewish scientists, researchers and artists to leave continental Europe. Freud was among them, moving from Vienna to London in 1938. (Several of Freud’s sisters were not so lucky, dying in Nazi concentration camps).

But Freud would have little time to enjoy his new home.

His smoking habit finally got the better of him. Cancer of the jaw caused him severe pain and doctors declared it to be inoperable. Freud wanted to commit suicide before cancer took his life, but he left the final decision to his daughter Anna. After being convinced there was no hope, she agreed to honour her father’s wishes. Freud’s doctor injected lethal doses of morphine into him, putting an end to his life at age 83 in 1939.

While criticised today, Freud can be credited with taking us out of the dark ages when it comes to mental health. Prior to Freud, anyone with psychological problems had no place to go, were treated as outcasts and sent to asylums. Doctors of the day would prescribe medication but Freud was among the first to actually listen to patients (viewed at the time as radical and insane).

Today, the legacy of Sigmund Freud teaches us that we can, and must, take responsibility for ourselves, feeding our minds with positive nourishment to realize our full potential.

Sigmund Freud’s cancer diagnosis took place 16 years before his death. During that time, he endured more than 30 surgical procedures and dangerous radium therapy. Despite his extended bout with cancer, he was able to write 20 books and continue his research. He fought cancer bravely and managed to remain optimistic and energetic. Those who knew him well, said Freud chose assisted suicide, not to avoid pain, but rather, to exert his independence – determined not to allow the disease to decide when he would go. The debate over doctor-assisted death continues today. Sigmund Freud is widely regarded as the founder of modern psychology.

[This post by Cory Galbraith first appeared on LinkedIn and has been reproduced with permission.]

{{#name}}{{name}}{{/name}}{{^name}}-{{/name}}

{{#description}}{{description}}...{{/description}}{{^description}}-{{/description}}

Note: We at Inc42 take our ethics very seriously. More information about it can be found here.