Inc42 Daily Brief

Stay Ahead With Daily News & Analysis on India’s Tech & Startup Economy

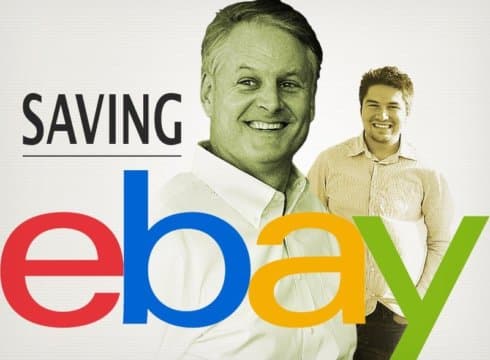

Back in the middle of the last decade, eBay, the massive auction site, was in trouble.

Between 2005 and 2007, its stock price was cut in half and its market cap shrank by $US30 billion.

In October 2007, eBay admitted that Skype, a company it had acquired for $US2.5 billion two years earlier, was actually worth less than half of that.

During the third quarter of 2007, eBay lost money for the first time as a public company.

Meanwhile, it was becoming clear that despite a massive early lead, eBay was going to miss out on China’s e-commerce boom. In the United States, Amazon was quickly becoming the “Everything Store,” thanks to smarter branding and superior technology.

After years of astonishing growth, the site was beginning to feel decidedly downmarket — a dotcom relic.

Her hand-picked replacement was John Donahoe. Like Whitman, he was bland-looking, blond, and exceptionally reserved. Like Whitman, he had made his career at Bain Consulting. In an industry dominated by visionary technologists, Donahoe, in his blue shirts and khakis, seemed to be a manage-by-the-numbers corporate drone.

Investors were not impressed with the hire.

From a high of $US58 per share on Dec. 29, 2004, eBay’s stock eventually sank to barely more than $US10 in 2009 — an 80% decline.

In 2010, eBay stock recovered some, but then it flattened out and stayed that way for all of 2011.

As the year ended, the company’s market cap was half what it was only a few years before.

How would Donahoe ever turn eBay around?

Jack Abraham’s taxi came to a stop.

It was Saturday night, Feb. 17, 2012 — around 7:30 p.m. Outside the cab, it was dark and in the low 40s.

Abraham had arrived at San Francisco Airport. He had just barely enough time to make his flight.

Still, he hesitated, momentarily glued to the seat as the momentousness of what he was about to do fully dawned on him.

“Are you crazy?” he asked himself, out loud.

In a few minutes, Abraham and five of his coworkers from eBay would board a 14-hour flight to Sydney, Australia.

Their plan was to spend the next two weeks re-inventing the eBay homepage, based on a rough idea Abraham had pitched to Donahoe only the day before. The CEO had warmed to the idea, and the positive response had sent Abraham into a manic frenzy of organising, recruiting, and planning. He had to move fast, he felt, because he feared that if he did not, eBay’s big-company processes and politics would suffocate his idea before it ever became a prototype.

Also, Abraham believed in moving fast. That was how he’d built his first company in his early 20s. It felt good to plunge right in.

But now, in that cab at the airport, the manic high had for a moment worn off, and Abraham was suddenly facing reality. The reality was his plan had a few problems.

Abraham listed them off in his head. For starters, almost no one at eBay knew what he was up to — including Donahoe himself. It was unclear who was going to pay for the trip. Abraham had gotten the six tickets to Sydney through eBay’s travel service, but technically, he’d never actually gotten approval. As for the rest of the trip’s costs, his plan was to foot the bill and then expense it. Maybe they’d sign off, maybe they wouldn’t.

Then there was the little matter of where he and his team would sleep. There was a possible Airbnb apartment, but no confirmation.

And the project itself? It was still a little fuzzy. Abraham had an idea, but not much more than that. There were no mock-ups to follow, no orders from above.

Finally, there was his day job. The eBay homepage was not his responsibility — or even close to it. His job was to run eBay Local, and for two weeks, he’d be blowing it off. Hundreds of emails were going to pile up. Phone messages were going to be ignored.

Meanwhile, it wasn’t as though everyone at eBay was going to love the idea of a kid in his 20s, with no authority whatsoever to do so, taking a sledgehammer to the homepage. The trip was going to make him lots of enemies and leave him exposed. He could already imagine the whisper campaign. Did you hear about that obnoxious 25-year-old kid who thought it would be a good idea to fly six people to Australia to live in a luxury penthouse for two weeks on the company’s dime?

There were ways of doing things among eBay’s old guard, and this was not one of the ways.

A career that started at 13

Jack Abraham has always been prone to manic bursts of risk-taking and productivity.

Without them he would never have landed at eBay in the first place, much less ended up a multi-millionaire at 24.

Jack Phillip Abraham was born Feb. 23, 1986. He grew up in Virginia, in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. His mother, Millicent, was an amateur artist — a poet and a musician. She divorced his father when Abraham was a child, and died of ovarian cancer when he was 16.

Abraham’s father, Magid, grew up on a small farm in Southern Lebanon before going off to school in Beirut when he was 13. From there, he went to engineering school in France, and then MIT. Today, Magid is the co-founder and CEO of comScore, a publicly-traded Internet analytics company with a market cap around $US1 billion.

Abraham says he grew up wanting to be president of the United States. Magid remembers Jack being “enterprising” from a very young age.

“When he was 3 years old he would go and talk to his friends, and he would convince them to exchange an old quarter for a shiny nickel.”

Abraham started working for his father and comScore during the summers when he was 13. He learned to code and how to work with people who were decades older than him.

Magid marveled at how his son would occasionally point out that someone he was working with could do their job better if comScore had a different process in place, or a different organizational structure. Magid would make a change, and soon the group was working “a lot faster and easier,” he recalls.

When Abraham was 16, the bursting of the dotcom bubble almost took out comScore. Abraham remembers being on vacation to North Carolina’s Outer Banks with his father, who spent the whole trip on the phone all the time sounding “really stressed out.” Abraham later learned that comScore only had two week’s worth of cash left in the bank, and that his father was desperately trying to raise investment capital.

After graduating from Langley High in McLean, Va. in 2004, Abraham attended the University of Pennsylvania, studying technological entrepreneurship at the Wharton School. There, Abraham joined a secret society and took a leadership position with the College Republicans.

He also built an e-commerce startup.

Milo, as he called it, began life in 2007, Abraham’s junior year. That spring, both he and his Wharton roommate, Nat Turner, won separate $US10,000 investment grants from Wharton. The grants came with an important stipulation: The recipient had to use the money to start a business.

Abraham and Turner rented an apartment in North Philadelphia that could double as an office. Turner’s business partner, another Wharton junior named Zack Weinberg, joined them. They bought desks from IKEA and crashed on Aerobeds under the office’s conference tables. The place was full of dirty laundry; cereal boxes were flung everywhere. There was no air conditioning. There were shootings in the neighbourhood at night.

One night that summer, the friends decided they were in it together. Turner and Weinberg gave Abraham a 5% stake in their company. Abraham, in turn, gave the pair 5% in his.

The new entrepreneurs all quickly came up with big ideas for their startups. Turner and Weinberg decided to build apps for the newly opened Facebook platform. Abraham wanted to build a smartphone website people could use to compare online prices while shopping in retail stores.

Late one summer night, after a long session of white-boarding, Turner and Weinberg decided to take a trip to California, where they could pitch their idea to venture capitalists. Abraham tagged along.

Turner and Weinberg were soon glad he did. Even though they were starting separate companies, they attended investor meetings together. Often, Turner and Weinberg asked Abraham to pitch their companies to VCs for them. The reason: even at 21, Abraham was an exceptionally polished speaker. He was good with eye-contact.

Then, as today, Abraham’s demeanor was that of a Fortune 500 CEO — albeit one who is surpassingly energetic and boyish-looking. He wore oxford shirts and khakis, or occasionally, a sport coat over a mock turtleneck. His thick dark hair was, and is, cut like a businessman’s.

After the trip to California, Abraham told his roommates he was finished with Wharton. That fall, Abraham set up several independent studies, so he wouldn’t have to actually go to class. Then he dropped out altogether, one semester from finishing.

Abraham had become obsessed with local commerce, and he’d begun to find people who might be willing to invest in his passion. In his typically impulsive style, he resolved to move to Northern California, hopping on a plane without the slightest idea of what he’d do once he arrived. He lived in a hotel for two weeks before finding a house in Palo Alto that could double as an office.

At the end of 2007, Milo launched — and then failed. It turned out shoppers who were already in a brick-and-mortar store were too lazy to put a product they wanted to buy back on the shelf, even if Abraham’s app indicated they could buy it cheaper online.

So Abraham quickly flipped his idea around, turning Milo into a search engine people could use at home to find out what products were in stock at local stores. Before long, this version of Milo started to gain traction. Abraham hired a dozen employees and filled a small office in downtown Palo Alto.

By 2010, Turner and Weinberg had even more radically pivoted their startup. Called Invite Media, it was now an ad tech company. More impressively, it was an ad tech company that Google coveted. On June 2, 2010, the news broke: Google had acquired Invite Media for ~$85 million.

Thanks to the 5% stake Turner and Weinberg had given him back in North Philadelphia, Abraham made millions of dollars from the sale.

Abraham took Turner and Weinberg out to dinner to congratulate them.

At the end of the meal, Weinberg turned to Abraham. “All right Jack,” he said, only half-joking. “This Milo thing better work out.”

That summer, one of Milo’s investors, Aydin Senkut, introduced Abraham to Mark Carges, the CTO of eBay. Abraham pitched Carges on a partnership that would give eBay access to Milo’s database of local store inventories.

Carges bit.

Then, six months into the partnership, a few of Milo’s investors approached Abraham to see if they could invest again in the company.

Abraham — who’d learned a few M&A tricks from watching Turner sell Invite to Google — decided to let eBay know about the investor interest, figuring it might trigger an offer.

Reaching out to an eBay contact, he asked for letter of intent indicating that eBay intended to integrate Milo data in its search results. “It doesn’t need to be blessed by legal,” he told the contact. “It doesn’t need to be legally binding. I just want to take this and show it to our investors so we can get a better valuation.”

Of course, the move had a secondary purpose: signaling to eBay that if it was ever going to buy Milo, now was the time to get it at a relatively cheap valuation.

Soon enough, eBay made an offer. Milo’s existing investors countered. eBay offered more.

“The valuation kept getting higher and higher,” says Abraham. Ultimately, he says, eBay “made us an offer that we couldn’t refuse.”

News of the deal broke in December 2010: $US75 million in cash. Abraham was only 24.

H2SO4/Flickr

Tearing into eBay

The first thing Abraham did when Milo joined eBay was piss someone off.

eBay had given the startup some prime office space on its Campbell, Calif. campus. But it was full of cubicles, and Abraham hated cubicles. So, at a meeting with all of Milo’s employees, he rallied the team to join him in tearing the cubicles down and tossing them out onto the lawn.

“I got a very angry call from facilities about that,” says Abraham.

But Milo had the home Abraham wanted. It was an old house near the main eBay building. There was a porch out back for weekly barbecues, and lean back chairs for lounging. An upstairs library with a fireplace became a conference room equipped with Nerf guns, an Xbox, and a Nintendo.

Over the next year and a half, the team built Milo’s technology into eBay. It powered a product called eBay Now, which enabled shoppers to use a phone to order a product from a local store and get it delivered in under an hour. The Milo team became known as the eBay Local team, with Abraham in charge. As it expanded, Abraham gave up his own desk. He liked to walk around. When he needed to sit to do work he’d take over the library.

That’s where he was when, on Feb. 10, 2012, he got the email from eBay CEO John Donahoe — an invitation to attend a meeting on the topic of “Innovation.”

It was this email that would, in just a week’s time, lead to Abraham sitting in a cab at San Francisco International Airport doubting his sanity.

At 9:30 in the morning on Friday, Feb. 17, 2012, Abraham walked into a conference room and sat across from Donahoe.

They were in a room in called “Bottom Line,” inside the headquarters of PayPal, an eBay subsidiary.

The room was all whiteboards and glass, light and chic and modern. At the far end, there were two large TV monitors. On one screen floated the head of eBay executive Guy Schory, teleconferencing in from Israel. There were three or four other actual people in the room. One of them was Andy Palmer, who’d only graduated from Wake Forest University in 2008, but was already a senior manager responsible for the “buyer experience” across several eBay products.

For an hour and a half, the group talked about ways eBay, a company with 30,000 employees, could get better at innovating. They talked process.

Then, at the end of the meeting, Donahoe asked the group if they had any actual specific innovations in mind for eBay.

Abraham had an idea in mind.

Back when he was running Milo, he’d had the idea that users should be able to follow retailers, brands, and product categories the way you can follow people and brands on Facebook and Twitter. He envisioned a feed where shoppers could see the latest updates from those brands and retailers — about new products or sales — just the way they can see updates from their friends in the Facebook News Feed or in the Twitter stream. Perhaps this kind of feed could replace the Sunday circular, which was going the way of the newspaper.

When Abraham sold Milo to eBay, he immediately hoped to implement this idea on eBay.com. But he very quickly learned that it wasn’t going to happen. For starters, he had a full plate integrating Milo’s technology and staff into eBay. Then there were the intra-company politics: Abraham was in charge of eBay Local. He had no authority over eBay.com, and the people who did had ideas of their own.

Suddenly, Abraham had his opening. He took it.

eBay should have a feed like the Facebook News Feed, he told Donahoe. Except instead of displaying updates from friends, it could show updates from eBay sellers and product categories. Best of all, he noted, eBay could turn the feed on without waiting for users to start following anybody, since it already knew search and shopping histories.

Slowly, the rush of energy that sometimes seizes Abraham started to course through his body. He was getting excited. The others in the room could hear it in his voice.

He went to the whiteboard at the front of the room and sketched out how the feed could transform the homepage. Donahoe and Palmer joined him up front, taking turns at the board.

Finally, at the end of the meeting, Donahoe came to a decision: “Alright,” he said, addressing Abraham and Palmer, “you guys have carte blanche to do this. Any resources you need, any money, any human capital, you’ve got it. The only thing that I ask is that you don’t tell anyone about what you’re doing.”

Donahoe directed them to work together for a few weeks developing a plan. Then the three of them would meet again to discuss the idea further.

As excited as he was, Abraham had a bad feeling about where “planning” and “roadmapping” would lead in a company of eBay’s size — to the slow death of his idea at the hands of the company’s entrenched careerists, who would naturally rally to protect their turf.

But here was a chance to really do something. If he could just move quickly.

Getting off-site … on the other side of the world

Palmer and Abraham met again that late afternoon, after most everyone else had gone home for the weekend.

They attacked a whiteboard, sketching out how the feed could work and what it would look like.

As the meeting wore on and the energy stayed high, Abraham felt a familiar mania taking hold.

Still, something was nagging him. Something was taking the edge off his exhilaration.

Donahoe had promised to give Palmer and Abraham whatever resources and staff they needed to build the feed. But organising a huge team was going to take time. There would be politics and bureaucracy. There would be PowerPoints.

Meanwhile, Abraham still had to run eBay Local. Palmer had a day job, too.

Abraham turned to Palmer. “How in the world are we going to pull this off?” he wondered.

That’s when it hit him: What if he and Palmer just took off — just grabbed a small team of the smartest people they knew at eBay and hunkered down somewhere to build the feed right away?

Abraham figured going to a far-away location for a limited time would accelerate the project. He thought about how JP Morgan used to take business partners out on his boat and tell them they had to reach a deal before coming back on land.

Palmer agreed.

Within moments, the two of them were at a laptop, scouring eBay’s internal site for offices around the world where they could work completely under the radar.

They came upon an eBay office in Sydney, Australia. A nice location was important: It would make it easier to persuade some of eBay’s best employees to cancel two weeks of their lives for a secret project with no shortage of obstacles in its path.

Around 5:30 p.m., Jack remembered he had to be somewhere. He had a dinner date with his girlfriend, Kathryn Fenner, and her friend at a Mexican place about an hour and a half away.

In the car, he started calling people, rounding up a team.

One of his first calls was to Chris Dixon in New York. Dixon, who had been an investor in Milo, had also been the CEO of Hunch, another startup that had been acquired by eBay.

Abraham asked Dixon for the names of two people, one in design, one in engineering, that would actually go to Australia if asked.

Dixon said he’d think.

Fifteen minutes went by. Abraham’s phone rang.

It was Dixon, and he had two people on the phone with him: designer Christina Mercando and engineer Ben Gleitzman. Abraham told them the story. They were in.

Abraham decided he needed two more people. The problem was, he’d arrived at the restaurant, and he and Fenner had a rule: no talking on the phone during dinner.

So while Fenner and her friend caught up, Abraham texted.

To Kyle Lee, one of the best engineers on the eBay Local team, he wrote: “Hey Kyle, it’s Jack Abraham. I’m working on a secret project authorised by John Donahoe and putting together a great team to prototype something awesome in the next two weeks. I’d like to offer you a spot on the team. Are you interested? It’d be in Sydney, Australia, and we leave tomorrow.”

He sent another to, Jason Kotenko, also an eBay Local engineer.

By 8:30 p.m., Abraham had a team.

There was Mercando, a user-interface designer from Carnegie Mellon who was also the head of product at Hunch. There was Gleitzman, an MIT graduate who, at 23, was one of the primary architects of the Hunch recommendation algorithm eBay bought for $US80 million. There was Lee, a self-taught programmer fluent in several coding languages, who Abraham says can “can crack any algorithm.” Finally, there was Kotenko, another self-taught coder — a “grease monkey,” as Abraham puts it.

That night, Abraham called up eBay’s travel service and booked six flights to Sydney.

The next day, still feeling the rush, he packed a small bag and took a cab to the airport.

As he waited in the security line, doubts lingered in Abraham’s head about the wisdom of the project he was about to undertake.

Then he got to the gate. He saw Lee, Palmer, and Kotenko. They were all standing around, apart from each other because they didn’t know one another. Then, each in turn saw Abraham, walking over all at once.

The rush came back. OK, Abraham thought, this is going to be awesome.

On the plane, everyone in the group was wired. Except for Lee. Abraham noticed that he was having trouble even talking. After some probing, Abraham learned that Lee had an intense fear of flying. He spent the entire 14-hour flight shaking and unable to sleep.

Landing in Sydney felt surreal. Since they had nowhere else to go, the group decided to head to the eBay office in Sydney and find a conference room.

Unfortunately, no one at the eBay office knew they were coming.

“Are you here to see someone?” the receptionist asked suspiciously.

Abraham leaned over the desk. “We’re actually here on a secret mission from John Donahoe,” he told her conspiratorially, “and we’d just love it if we could get a conference room for a few days. Could you possibly help us out with that?”

The receptionist looked at him blankly. “Who’s John Donahoe?”

After some back and forth, Abraham’s team finally found themselves in the spot they’d traveled half-way around the globe to get reach: a conference room with a whiteboard.

The group decided there were three things it had to figure out right away: what, exactly, they were going to build in the next two weeks, where they were going to stay in Sydney, and what were they going to call themselves. A careful student of business lore, Abraham knew the importance of myth-making, and naming the group struck him as a way of controlling the narrative.

The whiteboard filled up pretty quickly with concept sketches and interfaces.

Choosing a name was also easy. They settled on “Team Six” after the Navy Seal Team Six that had taken out Osama Bin Laden the previous spring. Abraham especially liked the name because it capped the number of team members, preventing others from later writing themselves into the story of how the eBay homepage got reinvented during a wild trip to Australia. Even before the prototype was designed, he was already thinking about how the story of Team Six would go down in eBay history.

There was more nervousness about the housing situation. People were feeling unmoored. With rooms in Sydney going for $US450 a night, Abraham and Palmer had already ruled out a hotel. They had found a place on AirBnB that looked incredible — an apartment right on the harbor in Sydney in a neighbourhood called Milson’s Point. It would easily sleep six, and it might even be a better place to work than an eBay office conference. Finally, they got the owner on the phone, and haggled him down to $US800 per night.

They arrived to find a two-level penthouse full of sleek, modern furniture. One entire wall of the living room was floor to ceiling windows with a view of the harbor. There was a pool on the roof. In the dining room, they found a beautiful table, ideal for entertaining, and everyone threw their laptops on it.

It was perfect, except for one thing. There was no Internet access.

Gleitzman, the 23-year-old MIT grad, got to work. His first idea was to run a blue Ethernet cord up the side of the building. But the apartment was on the seventh floor, and the cord didn’t reach. Finally, he ended up buying several 4G modems and WiFi routers to amplify them. The Internet in the apartment was never blazing fast, but it worked.

Over the next two weeks, Team Six hacked together a prototype.

Lee and Kotenko, the two eBay Local engineers, became inseparable. They both seemed to have coffee mugs glued to their hands.

After years away, Abraham tried his hand at coding again.

Gleitzman woke up the first morning there before 6 a.m. and ran across the entire city, mapping it in his head and building a two-week itinerary. It included a trip to the Sydney Zoo, a performance at the iconic Sydney Opera House, an open mic night and a nearby coffee house, and, of course, a Bush concert.

Mercando turned whiteboard sketches into designs in Photoshop. She also knit the team together, going out for one-on-one coffees with each of them in turn.

The trip was different for Palmer. He had lots of on-going projects back at eBay headquarters and he had to keep them moving through email and Skype. The time difference would help. Around noon in Sydney it would be midnight in California and the calls would finally stop.

The biggest technical challenge was getting access to eBay user data, which would power the feeds. eBay kept that data in different places that could be accessed through secret APIs. Fortunately, Palmer worked with those teams in California, and knew how to get access.

Team Six left the apartment in Milson’s Point for the last time on March 2, 2012, and headed for the airport. They’d done what they came to do. They’d built a fully functioning prototype of a reinvented eBay.com.

Abraham thought of it as getting first dibs on the world’s inventory — whatever your interests, you see relevant products the moment they arrived on the site. He was already thinking about how users would want to keep checking the feed throughout the day to see what had been listed while they were away.

For Abraham, the rush was over. Now all he had to do was show the prototype to his boss and hope he didn’t get fired.

Sorry John, there’s no PowerPoint

Five days after returning from Australia, Abraham had a previously scheduled one-on-one meeting with eBay CEO John Donahoe at Donahoe’s office. It was on Wednesday, March 7, at 10:30 in the morning.

Donahoe has an unpretentious corner office in eBay’s main building. It used to be a conference room. There’s no big mahogany desk or any ornate furniture in it — just a small table.

As he sat down across from the CEO, Abraham knew he was going to have to explain where he’d been for two weeks. Donahoe didn’t know about the trip yet, but people around the company were whispering about it.

“So,” Donahoe began, “that was a really interesting meeting that we had a couple weeks ago. How’s the planning going? Where are you in the process?”

Abraham smiled. “Actually John, immediately following that meeting, we recruited a team of six people, flew to Sydney and spent two weeks working on it.” Abraham opened a laptop with the prototype of the new eBay.com already loaded, and slid it across the table.

“And here it is,” he said.

Donahoe leaned forward to look at the laptop screen, and started clicking and scrolling around.

He was silent for what felt to Abraham like a very long time.

—

John Donahoe only reluctantly joined eBay in 2005.

He was reluctant because he knew that he was not like most executives who work at “hot” Internet companies.

“I’ve never been hot in my life,” he says.

Nevertheless, then eBay CEO Meg Whitman convinced him to join. Then, three years later, she picked him to be her successor.

Whitman knew Donahoe from her time at Bain Consulting, where he’d been CEO since 1999.

When he took over eBay, investors worried he would run the company like she had.

Quickly, he showed that he would not. He sold Skype. He laid off 1,600 people. He de-emphasised eBay’s auction business and started describing the company as a “technology partner” to retailers small and large. eBay added clients Home Depot, Macy’s, Toys ”R” Us and Target, helping them cope with a world dominated by Amazon.

These were smart tactical adjustments, and they’ve paid off. eBay stock is up to $US53 per share, tantalizingly close to its all-time high.

But beyond the tactics, Donahoe realised there was a deeper issue bedeviling eBay. It had stopped innovating.

For example, eBay never bothered to develop sophisticated search technology. This made it dependent on Google ads, which took a bite out of profits. And it made it hard for users to find products they wanted to buy, dragging down sales.

Likewise, eBay under Whitman never developed a product recommendation algorithm to match Amazon’s — despite the fact that Amazon credits 30% of its sales to the tool.

Partly, the issue was obvious: eBay had gotten fat and happy. For 10 years it had been a huge success, riding a wave of Internet adoption. During the mid-2000s, eBay was notorious for meetings that always ended in applause — even when the news was bad.

But eBay also had a problem attracting and retaining innovative, entrepreneurial people into its executive ranks.

Donahoe finally came up with a solution after consulting with eBay board director Marc Andreessen. Andreessen is best known as the creator of the first Web browser, Netscape Navigator. But in the years since, he’s become a powerful Silicon Valley insider. He sits on the boards of Facebook and Hewlett-Packard. His venture capital firm, Andreessen Horowitz, collects big-name industry operators as partners, and is considered the smartest money in tech. Mark Zuckerberg and Marissa Mayer call him a mentor. So does John Donahoe.

Andreessen is obsessed with the idea that tech companies need to focus on innovation above all else. He believes that the “output” of technology companies isn’t products — at least not the way the “output” of Ford is cars. The “output” of tech companies, he says, is innovation.

Andreessen’s second theory of innovation is that the people who are the very best at it are the people who create successful technology companies — founders. They are the people who have a proven ability to develop a concept and bring it to fruition.

For this reason, Andreessen believes that tech companies should be run by their founders.

The problem for eBay is that its founder, Pierre Omidyar, had no interest in running it. And Donahoe, a talented manager, had the wisdom to know he was not the kind of visionary who could found an innovative tech company.

So he decided he was going to have to go after the next best thing. He was going to have to build a team of founders, or founder-types, and give them the run of the place. He, meanwhile, would operate as their in-house consultant (and boss).

Since Donahoe became CEO of eBay he has acquired 34 companies. Thirteen startup founders currently work there, most in senior management roles. One is David Marcus, the co-founder of a startup called Zong. Today, Marcus runs PayPal, the company’s primary revenue and profit growth engine. Another is Tom Pinckney, the co-founder of Hunch, now in charge of the team who finally built a powerful recommendation engine for eBay shoppers.

Donahoe loves founders because they are crazy enough to rush blindly into projects that will require inordinate amounts of time and money — innovative projects that, by definition, rarely strike a typical corporate survivor as prudent ideas.

So, as he sat at the small table in his office clicking around Abraham’s prototype, Donahoe hadn’t the slightest intention of reprimanding the 27-year-old for his wild jaunt to Australia.

Instead he started laughing.

He looked at Abraham and said, “Jack, I think this could be the future of eBay.”

–

After Abraham’s meeting with with Donahoe, he and the rest of Team Six pitched the feed to the eBay board. The directors all loved it — but eBay’s founder, Pierre Omidyar, and Marc Andreessen were the most excited by far.

After the board meeting, Abraham stepped away from the project. Andy Palmer, another rising star, took over and shepherded it to life.

The feed became a central part of eBay.com, which 120 million people see every month. It’s made the site a more valuable tool, bringing increased sales and engagement.

“It was really the first step in driving a more curated, customised, personalised experience for eBay users,” Donahoe says.

eBay launched the feed 2.0 in October 2013. An eBay spokesperson says that since then, it’s seen greater engagement among users who have feed, including increased visits to eBay.com, more clicks on their homepage and longer eBay sessions.

Today, Palmer, still in his 20s, is eBay’s director of product management for the homepage. Christina Mercando left eBay to found a startup. She’s got funding from Marc Andreessen’s VC firm.

Nat Turner and his co-founder Zach Weinberg quit Google after a few years, starting another company they hope will help cure cancer. Turner realises the idea makes him sound crazy. “To be honest, most entrepreneurs are,” he says. “You basically go down a rabbit hole. Zach and I are down the cancer rabbit hole.”

Donahoe, who has hired a dozen Jack Abrahams, has become the constant subject of eBay turnaround stories. For good reason: eBay’s market cap is up $US50 billion since 2009. In December 2013, The New York Times published a long story detailing Donahoe’s innovative vision for the future of the digital wallet.

In the years since he formed Team Six, a lot has happened to Jack Abraham. He’s no longer at eBay. After the adventure to Australia, he realised operating a large division of a major company wasn’t for him. He wanted to spend the rest of his days bringing ideas to life.

In short, he’s less likely to ask himself out loud: “Am I crazy?”

He knows the strange manic rushes he gets into are something he should embrace.

“Every now and then I’ll come up with something so intriguing that I become completely infatuated with it which tends to lead to these situations,” he says.

“I go through them I tend to emerge more energized, rejuvenated and excited for what’s next.”

Sometimes when Abraham thinks about why he’s the way he is, he thinks about his parents. Certainly, he got some of it from his father, an entrepreneur himself. But he also thinks about his mother, a kindred creative spirit, who, when she died, taught him how little time he has to do everything he wants to do.

For now, the details of his newest schemes remain secret. But one of them, he says, was such a big idea he knew he had to get out of his everyday environment to get it done.

Soon, he was on a plane, bound for Australia

═══

A note on sources

═══

This story is based primarily on first-hand reporting, including interviews with Jack Abraham, John Donahoe, Chris Dixon, and Nat Turner.

As a part of the narrative, my story includes dialogue.

I am grateful to James B. Stewart’s “note on sources” at the end of his book, “DisneyWar.” That note helped me think about how to describe my own sourcing. In his note, Stewart describes how he sources dialogue. It’s a perfect explanation, and I’d like to quote it and use it as my own explanation.

“As part of the narrative, I have included passages of dialogue. Dialogue — what words were said — is a fact like any other. It is not necessarily a quotation from an interview with me and I would discourage readers from inferring that one or both of the speakers is a direct source. Especially in today’s world of instant communication, it is sometimes amazing how many people turn out to be privy to what others may assume is a private conversation. Many of the conversations reported in this book either took place before an audience or became known to a wide circle of people, often within minutes of their taking place. … In a few cases other people were listening in on speakerphones, extensions, or overheard conversations without one or both of the speakers’ knowledge. Readers should bear in mind that, given the vagaries of human memory, remembered dialogue is rarely the same as actual recordings and transcripts. At the same time, it is no more nor less accurate than many other recollections.”

═══

Bibliography

═══

Adams, Susan. “Milo.com Founder Jack Abraham and Father, ComScore Founder Magid Abraham: Is Entrepreneurship Inherited?” Forbes. May 6, 2011.

Cohen, Adam. “Going, Going, Gone: Meg Whitman Leaves eBay.” New York Times. Jan. 25, 2008.

Himmelman, Jeff. “EBay’s Strategy for Taking On Amazon.” New York Times. Dec. 19, 2013.

Mangalindan, JP. “eBay is Back!” Fortune. Feb. 7, 2013.

Mitchell, Russ. “eBay’s Lost years” The Bay Citizen. July 5, 2010.

Stewart, James. “Behind eBay’s Comeback.” New York Times. July. 27, 2012.

═══

Acknowledgments

═══

I’m grateful to Aaron Gell, who spent hours editing this story. Thanks to Jay Yarow for reading this story and suggesting edits. Mike Nudelman made the great cover image. Paige Cooperstein helped with hours of transcriptions. Elizabeth Wilke saved me with crucial copy edits. I’m grateful to Jack Abraham and John Donahoe for sharing their story.

{{#name}}{{name}}{{/name}}{{^name}}-{{/name}}

{{#description}}{{description}}...{{/description}}{{^description}}-{{/description}}

Note: We at Inc42 take our ethics very seriously. More information about it can be found here.