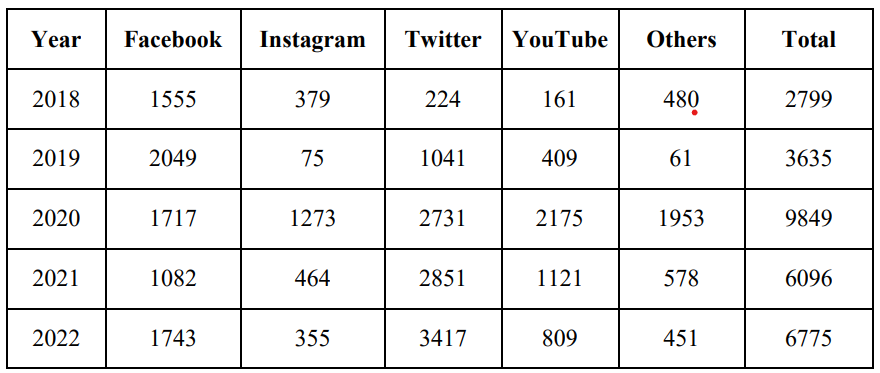

The government has blocked 29,154 URLs, including posts and accounts, since 2018: MoS IT Rajeev Chandrasekhar

In 2022, the government blocked 6,775 posts and accounts, up 11% year-on-year compared to 2021’s 6,096 blocks

Starting from 2020, Twitter was the platform served with the most government blocking orders, according to MeitY data

According to data from the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), the government has blocked 29,154 URLs, including posts and accounts, across Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and other social media platforms since 2018.

Minister of State Rajeev Chandrasekhar presented the data in Rajya Sabha in response to a question on censorship on social media by the government.

“The government policies are assured that ensuring an open, safe & trusted and accountable internet to its citizen,” said Chandrasekhar in a written response, adding that MeitY blocks content on the internet under Section 69A of the Information Technology (IT) Act, 2000.

Under Section 69A, the government can issue blocking orders to platforms like Twitter on the grounds of interest of sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of the country, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states and so on.

Starting from 2020, Twitter was the platform served with the most government blocking orders, according to MeitY data, followed by other platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and Instagram. Incidentally, the Elon Musk-owned platform accounted for nearly a third of all blocking orders issued in the past five years, with 10,264 posts and accounts banned on Twitter.

In 2022, the government blocked 6,775 posts and accounts, up 11% year-on-year compared to 2021’s 6,096 blockings. Last year, almost half of the posts and accounts blocked on the Indian internet were on Twitter.

The year 2020, however, saw the most pieces of content being blocked by the government, at 9,849, up 171% on-year compared to 2019.

To provide some context, 2020 saw the first lockdowns due to COVID-19 and there was a lot of misinformation being spread online as little was known about the disease, its symptoms and how it spreads. The increased need to check misinformation might have been the reason for a sudden spike.

Interestingly, the 2022 figures are still 86% higher than 2019.

When asked if there were any aggrieved parties which might have taken any recourse to a judicial remedy. To that, MoS Chandrasekhar said, “Yes, there are few instances where aggrieved parties have approached various courts in the country and cases are pending for judgement.”

It is prudent to mention that Twitter took the government to court in July 2022, seeking to overturn some of the content takedown orders the Centre had issued. The matter is sub-judice in the Karnataka High Court.

In the upcoming draft Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, there are certain aspects which might enable the government to bypass user privacy.

Sections 8(8)(9) of the draft Bill deems the consent of the data principal (the user) “for any fair and reasonable purpose as may be prescribed” after taking into account the public interest, the legitimate interests of a data fiduciary and the expectations of a data principal in context of the data processing in that situation.

The draft Bill has not clearly defined what ‘public interest’ means, which is a key concern expressed by many.

Ad-lite browsing experience

Ad-lite browsing experience